This is a continuation of the previous post linked below, but it’s basically a free-standing defense of why addict activism is crucially conceptually distinct from drug user movements.

Why not call yourselves “people who use drugs”?

In my several-part series I discuss the framework of addict oppression: the unique forms of marginalization levied against people with atypical relationships to substances and processes. The existence of this sort of oppression is why, I claim, we need a word for this group. I won’t make much argument that the word should be “addict” beyond what I said in the last post. (I don’t think there’s really any good counterargument that doesn’t follow one of the lines I describe.) But there’s one more point to discuss. In the last post I called it “2(b)” from my list, but here it is restated:

Why agitate for “addicts”? Why not use the term “people who use drugs,” or “PWUDs?”

Because that’s not the same community. Addicts =/= PWUDs. Some addicts don’t use drugs (gambling addicts, and drug addicts who aren’t in active use), and most drug users aren’t addicts. So the claim “We should use ‘PWUD’ as the designator” isn’t an argument that we should use an alternative word. It’s that the activist project should be changed dramatically in scope.

This is a popular position. Many people seek to eliminate the category of “addict” from the language entirely, especially any notion of addict pride, and describe the material wage of “addiction” as in fact a unilateral penalty of the carceralization of drug use across everyone who uses substances (or uses them sufficiently frequently, or uses street drugs, etc.). Often this is also associated with the view that celebrating abstinence is fundamentally opposed to liberation. Here’s an excerpt from an article that takes that angle:

Drug user movements actively call for a shift away from conceptualizing drug use in terms of “addiction”, as this approach has been used to pathologize, medicalize and criminalize drug users. These groups have highlighted that the language of “addiction” does not allow the space for real discussion of the myriad experiences of substance use in people’s lives…As many active drug users know, drug use is not inherently connected to “addiction” or problematic use, for example, 80–90% of people who use drugs do not have a problem with their substance use…Notions of “addiction” and the “addict” have been constructed over time by white, wealthy moral authorities such as religious groups, medical experts, psychologists, politicians, police and criminal justice systems.

Yeah. The concept of addiction was invented by “white, wealthy moral authorities” to pathologize people. Whoop-de-doo. So were the concepts of Blackness, and Deafness, and fatness. Then those categories were adopted by the mainstream, and the people they picked out were punished for belonging to them. Now they exist as forms of marginalization, and their members have developed identities and communities in light of that marginalization. They are groups that exist. Ignoring us will not make us go away; it will tacitly sanction our oppression. Seriously—imagine making this argument about any other oppressed identity.

But more to the point, these authors are just wrong in their initial claim that the apparatus of addiction was created to pathologize drug users. It wasn’t. (Do these people think all alcohol drinkers are oppressed for drinking?) It is true that drug user movements often argue addicts don’t exist and addiction was invented to pathologize drug use. But movements can be wrong, especially when they make claims about identities that aren’t theirs. Progressive rhetoric is often co-opted in order to redescribe others’ marginalization as an offshoot of one’s own. (Think about the way anti-trans activists frame trans men as women who are trying to escape misogyny.) Drug use has existed across time, but addiction is peculiarly modern; it is a product of the colonial mercantile age. It was built to facilitate two things: (1) the further subordination of already-marginalized groups (in particular racialized and colonized groups, not drug users monolithically), and (2) the economic exploitation and medical pathologization of a new marginalized category that overlaps substantially with the former: people whose consumption of drugs follows atypical patterns.

And even if the concept of addiction were created to oppress drug users, that would be irrelevant. The concept of low IQ was invented to restrict immigration, justify institutionalization, and control military recruits. Now it pathologizes plenty of people who aren’t involved in any of those auxiliary situations. “Well, we were the target first” is a misguided response to the fact that concepts intended to facilitate one oppression often instantiate new and varied others. The onus should not be on my community to defend that we exist, that our way of experiencing the world should even be expressible. That feels really insulting. “Well, the ‘addict’ category is a social construct devised by oppressive hierarchies.” I fucking know, man! But because that construct was devised, here I am, and if you snap your fingers I will not disappear. Using poststructuralism to magick away addicts’ material conditions is one of the clearest examples of the thing I call, to paraphrase Lorde, “using the liberator’s tools to assemble the master’s house.” Are we meant to deconstruct our way out of drug distribution charges? Stop turning liberationist language against liberationist aims!

Nonaddict PWUDs are not vulnerable to addict oppression in the way addicts are.

That’s not to say that PWUDs aren’t oppressed. Many people who use illegal or controlled substances are plenty oppressed, often in virtue of the fact that they use those substances. It compounds for members of other marginalized categories. But while there are policies important to agitation for both addicts and nonaddict users (i.e. decriminalization, safe supply), other elements of addict oppression are meaningfully unique. Nonaddict users generally don’t get civilly committed for substance use disorder treatment. They aren’t systematically refused medical intervention, or reported to CPS, for being on MOUD. Occasionally, this can happen by mistake, but they are not the category of person targeted by these mechanisms. One of the things that worries me most about modern drug policy is the increasingly popular position that recreational drug use is fine “so long as it doesn’t interfere with your functioning”—e.g. so long as your use isn’t “problematic.” That basically amounts to the claim that it’s fine to do drugs as long as you aren’t an addict! “Do drugs as much as you want, as long as you can use them responsibly” is intended to install progressive norms around nonaddicts’ drug use. It is not in any way conducive to addict liberation. It rules us out as an exclusion clause—like an afterthought.

An analogy I’ve used is telling a decarceralist that we shouldn’t invoke racial terminology when describing the carceral crisis. Imagine saying, “Actually, we should use the inclusive terminology ‘people who are confronted by the police.’ Anyone could be arrested!” I mean, sure, it’s true that (almost) anyone could be arrested. Black decarceralists never argued otherwise. But to interpret “We should isolate, and give voice to, the specific relationship between class, race, and carceral oppression” as meaning “We think white people don’t ever get incarcerated” is in blatantly bad faith. Sometimes it just feels whiny—“Name me too! I matter!”—but that’s not my real problem with it. My problem with this reframing is that it has materially bad consequences: it motivates equally agitating for groups that face oppression to different degrees. At best this is an ineffective distribution of resources. More likely, it actively backfires by making it such that the project runs out of contributors and ideas.

I wrote a post on here about intergenerational erasure: the systematic separation of marginalized communities from children as a manner of frustrating the creation of liberation projects that persist across time. If we focus on dismantling carceral oppression at a 1-to-1 ratio across every conceivable identity group, then the groups that face the oppressions to a greater extent will continue to be oppressed in larger percentages. It will still be, disproportionately, poor Black people who are incarcerated and therefore hindered from communicating their goals and plans across generations. As other communities become able to express their liberatory impulses, Black communities will remain at a hermeneutic disadvantage—more atomized and separated than other communities, until carceral oppression is over. But in such a case, carceral oppression will never be over. Its strongest opponents in the modern era have been Black activists. The momentum for decarceralism will be lost if this crucially important community that has led the anti-oppressive charge is not liberated.

This holds in general. Casual drug users did not devise the harm reduction project. Its architects were, by and large, addicts: the people most vulnerable to the harms instantiated by a structure geared toward oppressing them. If you still think there are no ways in which people with atypical relationships to drugs in particular are oppressed, think about these facts:

When a nonaddict is punished for their drug use, our explanation of why they were wronged highlights the fact that the victim is not an addict.

When someone is penalized for failing a drug test, we regard it as unfair only when the test was a false positive, or a result of prescribed medication, or a one-off.

When a person is arrested for drug possession, it is considered especially unreasonable if they had no priors.

The common argument against drug-testing welfare recipients is that it’s a waste of money because the positive rate is low.

Meanwhile, our negative reaction to hearing that someone was oppressed often goes away if we learn the person was an addict.

“Of course the hospital drug-tested this pregnant woman without her consent; she has a history of opioid addiction.”

“He was given low liver transplant priority because his liver disease is a result of alcoholism; that’s only fair.”

“Their parents had them involuntarily committed because their substance use was out of control. What else could the parents have done?”

Addict oppression is about identifying and punishing people whose substance use interferes with their being productive members of society. That isn’t just anyone who uses drugs. Yes, nonaddicts and addicts are both penalized by the fact that non-prescription opioids are illegal, and endangered by unsafe supply. But in a way untrue of nonaddicts, that fact makes it basically impossible for an opioid addict to have a stable 9-to-5, and much likelier for them to be homeless. As Sebatindira writes in Through an Addict’s Looking-Glass, the exclusion of addiction from disability legislation demonstrates that “the point is actually to penalise certain kinds of behaviour” (30). That’s the kind of thing Anna and I are trying to agitate against with the concept of addict activism. And it’s important to note that user movements often emphasize that most drug users retain social “functionality,” and in so doing exclude us. It’s all well and good to point out that drugs aren’t dangerous, but something more nefarious is going on with that claim. “Problematic use is rare” isn’t just saying drugs need not be dangerous. It’s openly stating that these movements aren’t agitating for us.

So the question is: Why? You’d think addicts and nonaddict users would have a lot of the same political goals. Why does so much rhetoric in favor of liberalizing policy and norms around nonaddicts’ use ignore or belittle us? I think the reason is obvious when you think about it. I’ve talked a lot in my other posts about the view that addicts put others at risk. In the progressive context, the meaning of “risk” is different, but that baseline perception isn’t: addicts’ existence threatens nonaddicts’ access to recreational or medical drug use.

Liberation is a zero-sum game

Earlier I said the “PWUD” descriptor makes little sense if alcohol counts. That would mean that if PWUDs are oppressed, then almost everybody in North America is oppressed. That can’t be right. Nonalcoholic drinkers aren’t oppressed in virtue of their drinking habits. (Sorry.) But excluding alcohol doesn’t make sense. It would (1) contradict the fact that there are extensive laws limiting time and place of alcohol use and transportation, (2) ignore the deliberate use of alcoholism as a justification for the oppression of racialized communities, (3) cut against the traditional exhortation of drug policy reformists that alcohol is a drug too, and (4) just be ridiculous.

Alcoholics are oppressed, but nonalcoholic drinkers aren’t. I think alcohol is a good flashpoint for the way in which a program of activism for addicts requires additional objectives not present in a program of activism for PWUDs. One obvious difference is that many alcoholics want spaces that are free from alcohol. (Also true for other addicts.) Another is that alcoholics have an interest in not hiking taxes on alcohol consumption; it comes—at a shocking ratio, look it up—at our expense. (Again true in general: drug decriminalization looks better than legalization by addicts’ lights because taxes come out of our pockets almost exclusively, and regulation mechanisms continue to carceralize us.) And sure, maybe addicts and nonaddict users aren’t totally opposed about this stuff. Maybe nonaddicts could take or leave dry spaces and tax hikes. (Although the authors of that article I quoted seem to be pretty unhappy about dry spaces.) But an example of a case in which addict liberation cuts against nonaddicts’ is priority in medical intervention. For an alcoholic to get a boost on the transplant list means nonaddicts get pushed down. For someone’s being on suboxone to stop counting against them in triage means it doesn’t count in a nonaddict’s favor that they aren’t on it.

Privilege is, in fact, a zero-sum game. That’s how oppression works. Liberation means that non-marginalized people lose some privileges, always.

A lot of people seem earnestly confused about why “there’s so much hate”—why those around them want marginalized people to remain marginalized. On the popular view, such resistance stems from either ignorance or else sincere hatred. But visceral hatred, I think, is seldom the motivation. Hatred help justify action; threat to one’s privilege motivates it. Non-unionists don’t want delivery drivers to suffer, exactly. Strikes (and more generally improving workers’ material conditions) are just dramatically inconvenient for them. Same with trans rights—the backlash often frames trans liberation explicitly as a threat to cis privileges. Undocumented people are competing for your jobs; Indigenous people have a claim to the land you think you own. Feminists argue that male privilege should not exist. Accommodating disabled people in public spaces is going to make life more difficult for abled people. And who, exactly, is going to pay for reparations to Black Americans?

It’s weird to me that this is widely denied. It’s obvious, and I don’t think my saying it is revealing an activist Secret. It’s not like I have 20,000 readers, and anyway, everyone who is agitating against the liberation of marginalized groups already knows the tradeoff is zero-sum. That’s why they’re against it! Why else would they care?

I’m not saying “Be nice to racists; they hate you only because they want an excuse to continue profiting at your expense, which isn’t as bad.” It’s just as bad. In fact it’s worse! There is almost nothing on earth less sympathetic than the selfishness of being unwilling to take even a scratch so that people crying out for freedom can breathe. But it is often important to try to isolate what the fear associated with liberation is, exactly. Identifying what privilege the non-marginalized group seeks to maintain tells us what liberation for the marginalized group would look like. Collective problem-solving does in fact require individual action; it just requires that the action be organized, and figuring out what the privilege at hand is tells us what to do. It’s become increasingly popular to say that individual interventions to reduce climate change don’t matter because 70% of emissions are produced by conglomerates or whatever. But that doesn’t mean individuals don’t have action items. It just means the action items are about one’s relationship to the culprits of climate change rather than one’s relationship to climate change itself—more like “boycott XYZ” than “use paper straws and take four-minute showers.” Or consider animal liberation. A lot of vegetarians are unwilling to say that meat is delicious because they know it’s morally repugnant to produce it. The modus tollens seems to be that if you eat meat, you want animals to suffer. But that makes no sense. Almost nobody is really into the idea of animal suffering in the abstract. Claiming that’s the case is diagnostically mistaken and leads animal liberationists to distribute their resources ineffectively. Resistance to liberation basically always stems from desires that would be frustrated by its achievement, in this case eating meat. Eating animals is a privilege that should never have existed in the first place, but now it does, and animal liberation means you lose it! I think that is why the cultural sensibility toward livestock animals is that they don’t have interests or emotions or futures or selves of any kind. The excellent foundational texts in animal liberation indeed stem precisely from the consideration of animal selves and futures. As they should! That is the relevant point to press. If we instead try to convince people kale tastes better than animals, they will know we are lying. There’s a reason the concept that liberation could be achieved without penalties to any group sounds too good to be true: it is.

So let’s investigate the “most people use responsibly” argument. Where else do we see claims that the vast majority of people do something without getting hurt? Negotiations of liability. It’s usually accompanied by a list of things you can do to prevent yourself from being harmed: make sure you have the proper equipment and training. Obviously, when companies issue these sorts of notices, it’s meant to characterize harm as your own fault—the fallen rock climber can’t sue. But there’s a deeper sort of damage control too. If the rock climbing wall is unsafe, then it should be shut down, and nobody should have access to it. Attributing harm to individual misuse of resources ensures everyone else can enjoy continued use of the rock climbing wall.

Societal hatred of addicts is, and has always been, grounded in the concept that we can’t use drugs “responsibly” and therefore will ruin access to them for everyone else. The idea is that God, or the government I guess, is giving us a trial run of Substances. So we must be perfect. Otherwise, the powers that be will yank the drugs away like a vindictive preschool teacher who cancels recess for everyone because Johnny misbehaved. That’s why chronic pain patients go to great lengths to separate themselves cleanly from us. (“People who responsibly use opioids for chronic pain aren’t addicts.”) The objective to instantiate some demarcation, to identify the Good Users who shouldn’t be indiscriminately punished when the carceral-clinical fist rightfully comes down upon the addict, is why the notion of “responsible medication user” exists in the first place. Anti-addict hatred springs from the fear that drug-use privilege can be revoked—that our being around poses an existential threat to nonaddicts’ access to drugs.

This comes across in the rhetoric of people who openly hate addicts. But it’s also clear in the way progressives talk about us. Recall the excerpt above: “80–90% of people who use drugs do not have a problem with their substance use.” You can almost hear the scream, “We’re not like them! We’re good about it; we’re adults.” And these people are ostensibly anarchists! It’s odd, really. People roll their eyes at that adage “you can have my gun when you pry it from my cold dead hands,” then turn around and say the same for alcohol and weed. Leftists who are eager to inform each other that consuming bananas is immoral never make that point about drugs—even though there are obvious regards in which the manufacture and transportation thereof are generally at least as ethically problematic as those of almost anything else I can name except animal products. Even the people willing to give up various and sundry modern comforts to bring about a better world shirk at this. And—obviously—I’m not claiming prohibition is necessary for, or even compatible with, addict liberation. I’m just saying that the extent to which substance-free culture is unthinkable to nonaddicts is just as much a motivator of addict oppression as puritanism. The unimaginability of losing access to drugs meshes with the cultural concept of addicts as people who threaten that access; the combination makes our liberation unacceptable.

This is what I think nonaddict user movements have gotten wrong. Anti-addict fear isn’t about the fact that we use drugs. Most people do that! It’s about the fact that our patterns of use are anomalous, attention-drawing, a spectacle. We’re the baby in a slasher movie who starts crying and reveals the group’s location to the killer. We are going to miss our foul shot and the whole basketball team will have to run a lap as punishment, because the coach is just that punitive. I could write a thousand more analogies; I think about this all the time. I’ve been acutely aware of this you’ll-spoil-it-for-everyone mentality since my teenage alcohol use was first weaponized by a penal body against the also-illegal-but-not-as-dangerous alcohol use of other people. It is because of people like me that Prohibition happened. Same with the widespread gambling bans of the early 1900s. And now the discourse of the day is that opioid addicts—fentanyl addicts in particular—are threatening others’ access. Nonaddicts who use drugs are not uniquely able to think around the fear induced by the notion that addicts will get drugs taken away from everyone. I worry they’re especially vulnerable to it.

There are people who are sincerely against all drug consumption. Maybe that seems to cut against my point. But ask those people why they’re against drugs, and bingo. Sooner or later it will become evident that their ultimate fear is of addicts—existing, and behaving in the ways we tend to. Nowhere is this clearer than in the silly exhortation that cannabis is a “gateway drug.” The puritans’ basic fear is that addicts are physically or psychologically threatening, and a drug-liberationist world will allow us to exist. Their privilege is safety, and we are unsafe people. And in particular, we are unsafe to their children: putting meth in their Halloween candy or whatever. Come on—do you really buy that temperance activists are afraid of some guy smoking marijuana on his porch? It makes much more sense that their worry is that a world in which some guy is smoking marijuana on his porch is invariably also a world in which addicts are out and about: some taking pride in their drug use and others taking pride in their abstinence, and one sitting here writing this post, telling them that the pride they feel in both those things is justified.

In conclusion

I think it’s no accident that the vast majority of the people who tell me that I shouldn’t refer to myself as “addict” are not members of that identity category.

I think it’s no accident that the medicalization of addiction, ostensibly providing a blame-free lens, just finds a different thing to blame addicts for: not getting help.

I think it’s no accident that so many decriminalists—not unlike prohibitionists!—want to view the “drug crisis” as monolithic, instantiating equal harms across race, class, and, yes, addict lines. I think this reflects that (1) the addict community has interests different from theirs, and (2) bringing attention to us threatens their access to the stuff they can “use responsibly” but we can’t.

Many addicts describe their relationship to their substance of choice in terms of a binary: active addiction or total abstinence. That’s criticized a lot. It’s called self-hating, prudish, or an endorsement of addiction medicine (it’s none of these). I think the problem, really, is that people who (correctly) think drugs should be legal believe describing this binary is counterproductive to their objectives. But the fact that such a binary exists for some people is totally compatible with a world in which others use drugs to the extent they want to. In a way that is not true of large-scale political policy, whether I allow alcohol or heroin or gambling in my house does not affect you. Small-scale dry spaces do not problematize the decriminalization project.

I think it’s unreasonable to call people self-hating or insufficiently subversive or whatever while remaining broadly uncritical of how your objectives produce the world that compels them to develop the behavioral patterns you call self-hating. So if you think sober communities will lead to authoritarian trickle effects, recall that the group you’re critiquing consists of people who are systematically led to believe the only acceptable relationship they can have with their drug of choice is total abstinence. Addicts—people whose experience of use is not “controlled” in the way nonaddicts consider their own—are much more likely to be carcerally apprehended for their use, whereupon they get court-ordered to the very twelve-step groups that promote abstinence-only recovery! Remember how drug user and chronic pain movements have operated largely by distancing themselves from or denying the existence of these people. Then think whether maybe the fact that so many addicts are strict teetotalers who religiously avoid triggers has nothing to do with self-hatred and is in fact a survival mechanism.

User movements alone cannot transform the conditions of addicts, because they are not demanding the radical acceptance of atypical relationships to drugs. While keenly aware that marginalized people are more likely to be viewed as having atypical relationships to substances, they do not reject the view that such atypicality is fundamentally pathological. Rather, they say: Some patterns of use that appear to be atypical actually aren’t; we interpret them that way because the user is marginalized. But the only reason anyone would bother to argue this in the first place is if they think the existence of addicts is untenable—that marginalized people aren’t worth advocating for if they’re addicts. Addiction becomes a perfectly isolated construct that, while fashioned to oppress, doesn’t actually describe any real people. Of course this view doesn’t have the resources to answer the question of how we ensure addict flourishing. It’s founded on the notion that we don’t exist, that people can use drugs without problematizing their “functionality.” (And yeah, of course “functionality” is itself a construct inseparable from the economic system under which we live, but nobody seems interested in critiquing that the way they critique the addict category.)

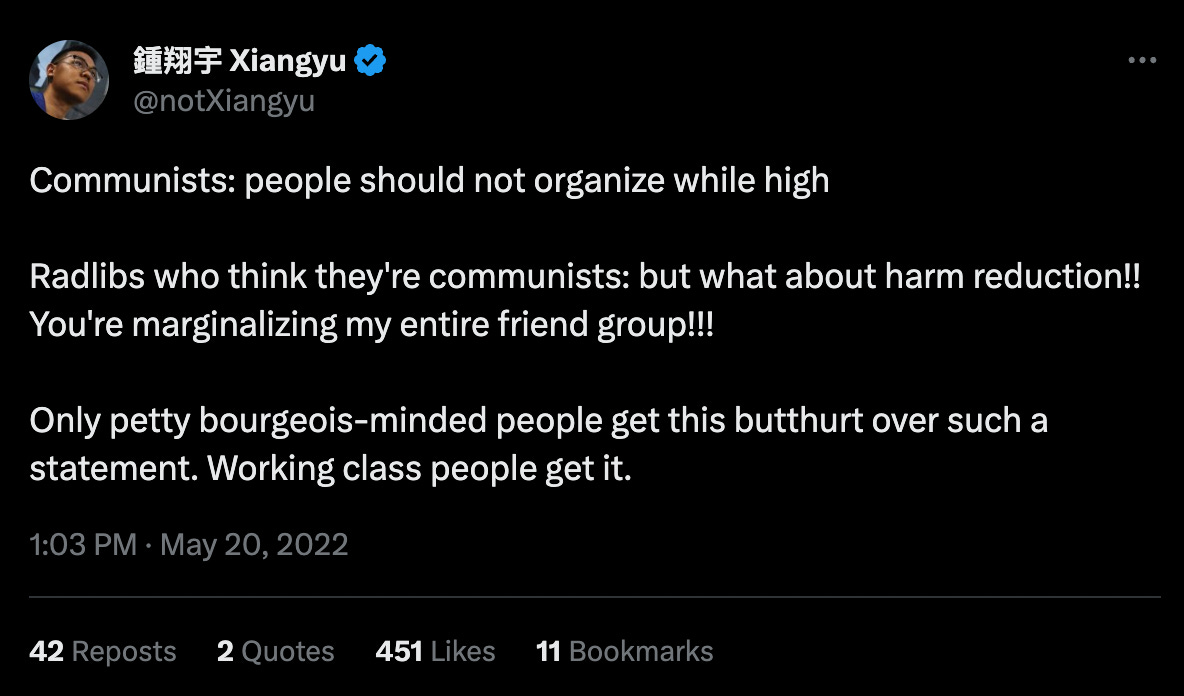

There’s this canard that addicts in active use have objectives totally incompatible with those of abstinent addicts. Actually those two groups work great together when it comes to agitation, as the history of harms reduction movements show. But neither group is welcome in nonaddict user communities. Don't organize while high, but also fuck you for wanting dry spaces. Just go be somewhere else.

I think that gets to precisely the point. Underlying a lot of the rhetoric that seeks the elimination of the addict category is the desire to erase the abstinence/excessive use binary, to coax addicts toward a middle ground. Don’t use drugs in the unusual fashion you do, but also don’t be abstinent, that’s prudish and weird. Goddammit, why can’t you just be normal? We must listen to and learn from the theories about drug use propounded by people who’ve gone to comical lengths to convince puritans that they’re nothing like us. We are told that sobriety is repression by the same people who levy the talking point “Most people who use drugs do so responsibly.” But that entails there’s a right and wrong way to use drugs. So much for subversiveness! You cannot challenge normativity while imposing it.

The earnest claim that most people do drugs correctly raises the question: do you think addicts should do drugs or not? When we don’t, we’re decreed insufficiently transgressive. When we do, we’re viewed as liabilities whose dangerous drug use will get you in trouble. The reason this is ignored in discussions of the subversiveness of drug use, I think, is that for most nonaddict users, there just aren’t addicts in their imagined utopia. It all gets back to this nonaddict theory that addicts are broken nonaddicts—what I call “Normal Person Plus.” We’re driven to atypical use by an inability to cope with trauma, or Madness, or capitalism. Fixing everything else will fix us, because addiction is fundamentally a manifestation of suffering. So in a way untrue of many other identities, there cannot be any such thing as addict joy. When liberation is achieved we won’t exist, because we never should have existed.

To that I say, here I am.