Addict oppression: the (medical) resource gap

Medical resources available to nonaddicts are withheld from addicts.

Below are the previous entries in this series.

That last one was the first half of what I call the resource gap: the systematic denial, in virtue of addict status, of assistance granted to otherwise-similar nonaddicts. Onto the second half: medical instantiations of the resource gap.

Lower priority in medical intervention

Addicts receive systematically lower priority in, and worse, medical care than nonaddicts. For instance, almost half the patients in need of liver transplants have alcoholic liver disease, but people with ALD make up only 15-20% of liver recipients. A famous 1991 paper by Moss and Siegler made the case that “patients who develop end-stage liver disease through no fault of their own should have higher priority for receiving a liver transplant than those whose end-stage liver disease results from failure to obtain treatment for alcoholism.” This applies as a blanket claim: any patient whose liver failure is attributable to alcohol use should be able to access a transplant liver “only if there are no nonalcoholic patients who could benefit from the same liver” (Benjamin, 338). This is a publicly popular position: a subsequent opinion survey found that family doctors, gastroenterologists, and the general public alike relegated people with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) to extremely low priority when ranking lists of potential liver recipients (Neuberger, 173). Modern surveys product similar results. A 2021 paper by Grubb et al. finds that among a population of participants recruited online, “ratings for acceptability and priority [of organ transplant and resuscitation] for persons who had a SUD were generally lower than ratings for other conditions.” Young addicts are less likely to get transplants than their nonaddict peers. Surveys recommend screening transplant patients for addiction.

All this is pretty well-established. As with family separation, I don’t need to convince you it happens; you know that. I need to convince you it’s bad.

The six-month rule

Alcoholics in the U.S. are widely required to complete a period of sobriety before being put on the transplant list. It’s often called the “six-month rule,” and supported by a variety of justifications. Six months’ remission gives the liver time to recover before transplantation, improving health outcomes. Six months’ remission predicts long-term remission, which is conducive to better health outcomes.

From these sorts of explanations, you’d believe not drinking for six months is a panacea. But in actuality, the idea that the six-month rule predicts sobriety or transplant success is groundless. A famous 2011 study by Mathurin et al. of European patients found that six-month survival rate was dramatically higher for earlier alcoholic transplantees—and that this benefit persisted through two years. Saliently (though this doesn’t entirely explain the health outcomes), more than half the people with severe alcoholic hepatitis do not live for six months after diagnosis. A 2018 study by Ma et al. reinforces the conclusions of the 2011 article: transplanting early “yields survival outcomes comparable to liver transplantation for other indications.” Other studies have similar findings.

This is widely known. It was known at the time of Moss and Siegler’s writing. Yet even the doctors who describe ALD as “an excellent indication for liver transplantation” acknowledge that providing livers to alcoholics is a “controversial use of resources” (Bellamy et al., 2001). Something else must be going on here, because relapse (which occurs in up to 40% of cases!) does not substantially affect survival rates among alcoholic liver transplant recipients. There is a sort of intuitively obvious point here, which holds with only a very small number of exceptions: It simply isn’t true that people drink their way through two livers.

Medical desert

Recall that in discussion of both the carceral-clinical seesaw and intergenerational erasure (and in my published work), I claimed that people tend to think the feature that does the work in explaining why addicts should be subjected to these things is desert or blameworthiness or moral badness, but actually that’s incorrect. Or at least it’s the improper attack point for an addict liberation initiative, because it is strictly more than a defender of these oppressions needs to justify our subjection to them. Actually, the relevant justification is that addicts are dangerous. We don’t have to be bad people on this view. We just have to be bad at stuff: staying out of trouble, interacting normally in social contexts, childrearing.

I’ll apply a similar demarcation here. People often assume that the question of addicts’ medical priority—usefully metonymized as “should alcoholics get liver transplants”—hinges on a moral desert question. But it actually doesn’t.

Now, the claim that alcoholics are less deserving of liver transplants than nonaddicts might mean two different things. First it might mean something about inherent moral badness. On such a view, we don’t deserve transplants for the reason that serial killers don’t deserve transplants: medical intervention constitutes an improvement of someone’s well-being, and people who are immoral shouldn’t have access to that. But that isn’t what clinicians think they mean when they say alcoholics don’t deserve livers. Rather, the reason we shouldn’t get transplants is the same reason that a sighted person who pushed a big red button reading “PUSH HERE FOR IMMEDIATE LIVER FAILURE” shouldn’t. Our condition is our own fault. You reap what you sow.

I am not inventing this distinction; the medical literature has been careful to make it. The Ethics Committee of the United Network for Organ Sharing in 1992 established three “general principles” for organ allocation: fairness, maximizing net medical utility, and patient autonomy). (This has been revised substantively and now makes no mention of “punitive”; the current text is available here.) It took great pains to establish that “punitive” exclusion from transplant priority was unacceptable, and not the justification for the low priority of addicts. From Benjamin’s paper:

The committee mentions ALD in illustrating applications of the principle of autonomy. Under the subheading of ‘‘Voluntary Behavior of Recipients,’’ the report explicitly rejects ‘‘punitive’’ policies that would categorically exclude medically and psychologically qualified patients with ALD from transplantation simply because of their past drinking. The report then raises, but comes to no agreement on, the question of ‘‘the nonpunitive use of this factor in allocating organs.’’ The issue is whether an ALD patient’s not having sought treatment for alcoholism should place him or her at a comparative disadvantage in competing for a new liver with nonalcoholic patients whose liver failure is more clearly ‘‘beyond their control’ (338).

What people think they think when they say alcoholics don’t deserve new livers is that alcoholics’ poor physical health, unlike that of nonaddicts, is their own fault. This line of thinking manifests in the asymmetric treatment of addicts whose need of medical intervention can be attributed to their drug use and those whose need can’t. For example, a recent survey of 42 transplant centers across the U.S. found that only one reported that it point-blank does not require abstinence from alcohol as a condition for eligibility, but virtually none required cessation of marijuana or cigarette smoking. And in Neuberger et al.’s opinion survey on attitudes toward liver transplant indications, the authors’ examples of other drug users facing liver failure carefully describe the liver failure as resulting from the drugs. “A 45 year old woman used drugs in the 1970s during which she contracted a virus which resulted in liver failure. She has not used drugs since.” (I’ll call her the “long-ago misuser.”) “A 17 year old woman takes a paracetamol overdose after a row with her boyfriend. It is the first time she has done this.” (I’ll call her the “youth.”)

So there’s an idea here that we could distinguish between punitive and non-punitive desert rationales for withholding of medical intervention. One type is an inherent-quality notion, a desert by nature. You shouldn’t get assistance because you’re a bad person. The other is a “well well well, if it isn’t the consequences of my own actions” concept: desert by anticipated result. My claim is that while this distinction is a nice story, a post hoc way of justifying why people feel the way they feel about addicts, it does not track with the empirics of social attitudes.

One line of argument supporting my claim is the maintenance of the six-month rule across clinics everywhere despite its controversial empirical efficacy (to put it lightly). The six-month rule, we might say, is a hoop addicts are forced to jump through not in order to improve their health, but in order to undergo a category shift into the group of people who intrinsically deserve medical care, in virtue of taking their health into their hands proactively. I might even add that the six-month rule satisfies a lurking pernicious purpose of barrier to entry, helping make it the case that addicts don’t live long enough to get the chance to compete for social resources. But whatever—that’s more than I need for my argument.

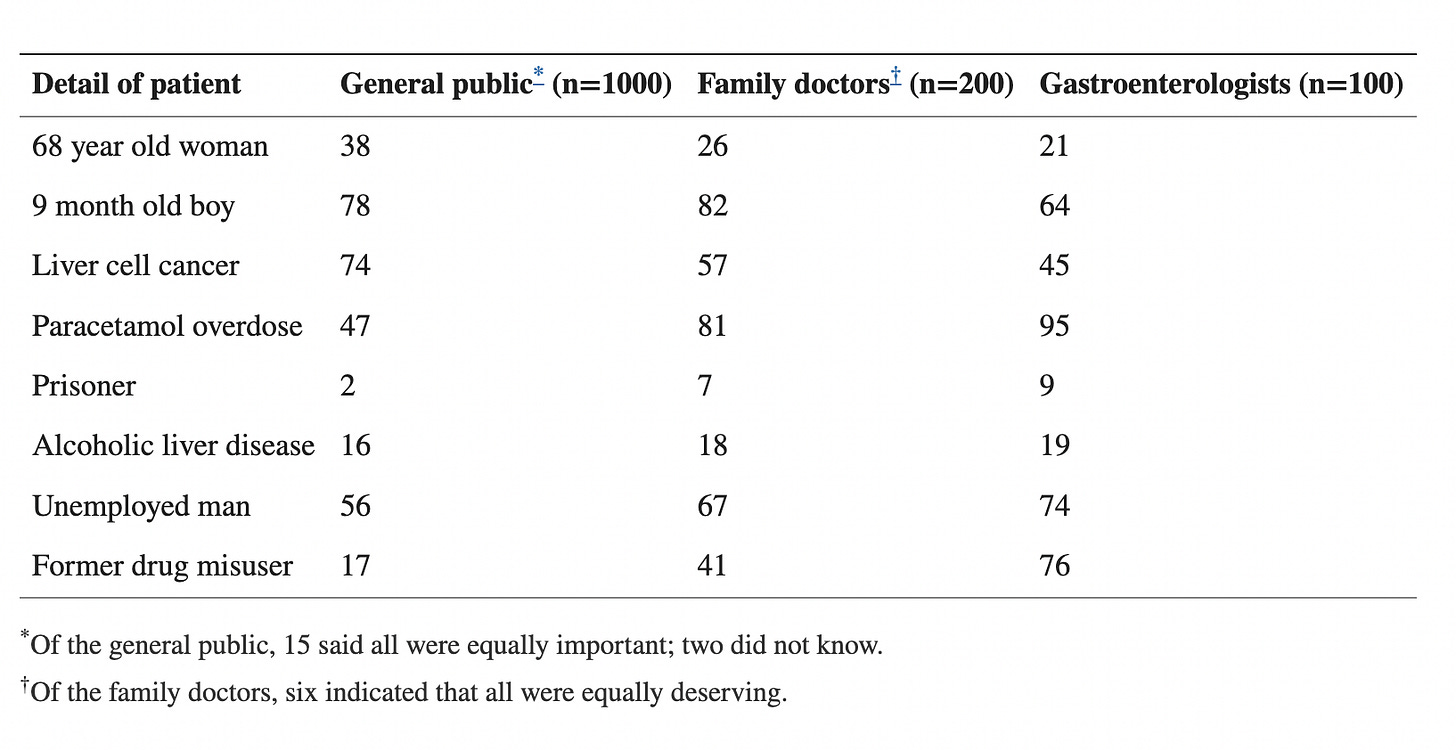

A second line of support is that the actual social attitudes about transplant availability for addicts do not behave as the desert-by-nature/desert-by-anticipated-result partition predicts. Take, for example, the following representation of the transplant priority among the people surveyed by Neuberger et al. The survey asked the three groups (the general public, family doctors, gastroenterologists) to allocate four livers among the eight hypothetical patients.

The above table shows some stark agreements and disagreements between the public and the doctors. First, everyone agrees that prisoners (their case being a “50 year old man…serving a long sentence for grievous bodily harm”) and alcoholics should get the lowest priority. This is the only commonality in the ranking across all groups surveyed. Second, the groups diverge dramatically in how they treat the other two drug users. Almost all the doctors think the youth should get a liver, but more than half of the public doesn’t. Likewise, most of the gastroenterologists think the long-ago misuser should, but less than half of the family doctors, and almost none of the public. (For my purposes here, the similar asymmetry for the “liver cell cancer” case is irrelevant—their example is of a pregnant woman who is extremely likely to die even with the intervention, and the salience of medical utility explains the different responses from the doctors and non-doctors. No prognostic claims like that are made about any of the other case histories.)

Tellingly, when asked which patient was least deserving of a new liver, the plurality of family doctors says the man with ALD. Among the gastroenterologists, the prisoner narrowly beats him out, but those two are uniformly ruled least deserving among all three categories. Yet while the public’s third choice is the long-ago misuser, the family doctors and gastroenterologists dramatically diverge. They disagree too about the youth—the doctors are much less likely to say she is least deserving.

These features—the low priority of the prisoner in all three groups and the distinction between the other drug users and the alcoholic—don’t support the nice distinction between desert-by-nature and desert-by-anticipated-result. They shatter Moss and Siegler’s rationale that “patients who have not assumed equal responsibility for maintaining their health…should be treated differently.” The two other drug users are also “responsible” for their liver condition under any plausible interpretation of what that word means in this context. The prisoner’s not! Sure, this is a decision problem of multiple objectives maybe, in which long-term utility has to be balanced against desert. The youth is 18 and hence has a longer life ahead of her; the prisoner is incarcerated and has limited access to a good future. But that doesn’t explain the disconnect between the deservingness of the alcoholic and that of the other “drug misuser”—a middle-aged woman whose liver failure is definitively resultant from her drug use. What actually explains it, I think, is that she’s not an addict. The authors frame it that way: her use was in the seventies (we’re given to understand by the cultural hermeneutics that everyone did drugs then) and stopped long ago, apparently without much need for medical treatment. The youth isn’t an addict either: “It is the first time she has done this.” But the alcoholic, obviously, is.

The mushroom reductio

Imagine a guy walks into the woods and, without thinking much about the risks thereof, eats a mushroom. It’s poisonous. He experiences rapid liver failure and needs a transplant.

This kind of thing actually happens, enough so that there’s a well-established literature on transplant outcomes for Amanita poisoning. But—and you can try it for yourself—if you Google “opinion survey mushroom liver transplant” you will find nothing. (A lot of case studies and meta-analyses of the success or incidence of such transplants will come up, but zero hand-wringing about moral deservingness.) If you Google “opinion survey alcohol liver transplant,” there’s hundreds of peer-reviewed articles. One of the top two is about ALD liver recipients’ opinions on public awareness of “alcohol-related health effects”; the other says that “the main criteri[on] for transplant in ALD should be the patient’s risk of return to harmful drinking.” Nobody is asking: “But what if the mushroom-eater goes out and consumes another one?”

There is no literature on whether Amanita-eaters deserve transplants because it does not occur to people that this use of livers is controversial. But of course the adults who fancy themselves self-taught mycologists and rashly eat an Amanita are responsible for their liver failure. It’s the patient’s own fault! And, as with the alcohol case, recommendations for public messaging about the dangers of consumption abound. The dramatic divergence in the literature perspectives seems spurious, because the cases are similar in many respects. The crucial difference: “accidental Amanita-eater” is not what I elsewhere call a baggage category. It’s not a kind of person, a grouping that cleanly demarcates a set of people on the basis of something common they share over and above what the descriptor strictly says. Nor is “person who used drugs in the seventies but doesn’t now.” But “addict” is. It’s not about the consequences of people’s actions; it never was. It’s about being a kind of person.

There is, of course, a counterargument, one that’s been around from the beginning. Moss and Siegler are careful to state that it is not being an alcoholic that merits low priority for transplant, but failing to seek treatment for alcoholism. Eating the mushroom is something you do once; continuing to “succumb” to addiction is something you do over and over again. The Amanita guy only screwed up one time. The alcoholic keeps doing so despite knowing the consequences, which must be on purpose.

My problem with this is that it makes reference to some way of separating different degrees of moral responsibility that the theory is not developed enough to actually deliver. Like eating mushrooms, years of drinking give some people liver disease and not others; there’s a luck element involved. On what grounds can we rule the first accidental and the second deliberate? Whence this notion that alcoholics, unlike the Amanita-eater, are taking all-things-considered decisive action, walking willingly down a well-paved road to hell? If anything, the fact that eating one mushroom can kill you, while taking one drink generally can’t, seems to mitigate responsibility in the second case.1

There’s a folk psychological distinction between things people sometimes call ego-syntonic and ego-dystonic behavior. Sometimes, we think, people do things for no reason, or for reasons that don’t track with deeper category memberships they have. They act against their ego. Other times, people’s actions reflect who they really are. Accidentally eating a poisonous mushroom, or using drugs in the seventies and then stopping, or even maybe overdosing on acetaminophen once, is just a mistake. It doesn’t convey information about the person beyond the fact that they did that. But being an addict does. The received view is that addiction is a continued self-defeating choice, at once against the addict’s will and also inseparable from who they are. Amanita-eating, by contrast, is a one-off. We don’t judge the person who does it because, like getting a speeding ticket, we presume it could happen to anyone.

But that’s not true! Eating the mushroom is saliently voluntary, and the moral desert argument totally ignores this. Speeding tickets really do happen to all sorts of people for all sorts of reasons, some of which involve bad luck. The Amanita-eating thing isn’t like that. Sure, it involves being in the wrong place at the wrong time. But there’s a very simple way to prevent it from happening to you: just don’t go out into the woods and eat wild mushrooms! To me it seems clear that preventing liver failure through wild mushroom toxicity is, like, an order of magnitude easier to do than preventing liver failure through alcohol toxicity.

The point is that distinguishing between ego-syntonic and ego-dystonic behavior, or otherwise arguing that Amanita-eating is a blip but alcoholism is a consistent, deliberate pattern of action, does nothing for my opponent here. Accidentally picking and eating a poisonous mushroom is a very idiosyncratic, atypical behavior. Most people don’t ever do this. I’d wager the set of people who do also shares features beyond just that. We could run studies on comorbidities between personality disorders and people’s tendency to go eat poisonous mushrooms by accident. We could ask accidental Amanita-eaters whether they experienced childhood trauma. We’d find, or create, all sorts of risk factors and dispositive influences.

But we have not done this. The reason why is that “accidental Amanita-eater” is not what Ian Hacking called a human kind. It isn’t an axis along which we partition people. That doesn’t mean we couldn’t! In a world that treats the Amanita guy the way we treat addicts here, we’d say his behavior stems from delusions of grandeur. He has cultivated self-aggrandizing perceptions of his ability to characterize safe fungi to eat, and this is a natural result of that. Of course, it’s difficult to imagine such a world, precisely because we do not conceptualize this sort of person in that way on a broad scale. We think of “accidental Amanita-eater,” like “Canada resident” or “Guinness world record holder,” as having no bearing on any other qualities people might have. Absent its conceptualization as a category, the set of Amanita-eaters isn’t directly marginalized in the way addicts are. We don’t place those people in settings where their tendency to eat mushrooms without carefully assessing their safety is exploited in a way that leads to downstream liver failure. They don’t see “Mushrooms here, some poisonous, eat at your own risk” kiosks as they walks down the street. But that is the situation for alcoholics. Pretending otherwise is not just cruel, but in transparent denial of reality.

Mickey Mantle

I’ve been trying to break down this distinction between kinds of desert, but earlier I implied that this isn’t really about desert at all. So, I want to end this section on liver transplants by clarifying how “people are considering alcoholics’ status as alcoholics rather than their direct responsibility for their liver condition” and also “the reason for alcoholics’ low transplant priority isn’t that alcoholics are regarded as bad people” can both be true at once.

Remember Mark Siegler, from the paper I’ve been referring to throughout this section? He implied that alcoholics should be placed categorically lower in transplant priority than other patients. But, interestingly, Siegler thought differently about the case of alcoholic baseball player Mickey Mantle, who needed (and received) a liver transplant. He wrote that “we have to give deference to the rare heroes in American life,” that we need to “take them with all their warts and failures and treat them differently.” Mantle, who “captures the imagination of a generation through his skill and ability and personality,” should receive a transplant, Siegler claimed.

This is contextually bizarre, for Siegler is adamant that money and status should not determine transplant priority. It would be incorrect to say he thinks Mantle deserves a transplant because he is morally good. That’s not what actually does the work. The reason physician and public attitudes toward alcoholic recipients of liver transplants resemble the way they’d look if desert-by-nature were the relevant factor is that they actually track something that is a good proxy for it, and also a good proxy for being an addict (although in the case of Mickey Mantle the two come apart), which is that addicts are perceived to be miserable people.

Neuberger et al.’s long-ago misuser and youth get transplants. The alcoholic and prisoner don’t. (The idea that the mushroom-eater shouldn’t doesn’t even occur to anyone.) What explanation can track all these attributions? The underlying conceit, I think, is that addicts do not lead good lives—not in a moral sense, but in a value sense. Ours are the lives no one would want. Crucially, alcoholics who are in need of liver transplants may have good health outcomes if they receive them, but will not stop being miserable. This isn’t true of the long-ago misuser, or the youth, or the mushroom eater, or of a few well-positioned addicts like Mickey Mantle. But it is true of the incarcerated nonaddict.

The literature on addiction is insufficiently critical of the basic premise that addicts are unhappy people. The received views generally divide into two camps: disease and choice theories. On the former, addiction is the behavioral presentation of a deep-rooted, insidious sadness; an experientially terrible Madness; unfixable early childhood trauma; or some other objectively undesirable and uninhabitable interiority. So, obviously, on this view addicts are constitutionally unhappy. But the choice view is no different. If drug use is freely, rationally chosen, then what does that say about the addict’s use by the lights of revealed preference theory? That the alternative is worse!

“Patients who have primary alcoholism and get substance abuse treatment are far less likely to relapse than patients who have alcohol and poly-drug addiction. ‘The first group is a happier group,’ [said a psychiatrist.] ‘The second group tends to have had unhappy childhoods and adult personality disorders’ that make recovery harder.” -Gale Scott

I AM BEGGING NONADDICTS TO STOP TAXONOMIZING TYPES OF ADDICT INTERIORITY

Why, then, the exception for six-month-rule-following alcoholics, or for people desperately trying to get substance use treatment? Well, maybe alcoholics who attempt to seek help have a shred of light shining through. They conceptualize the good life as something accessible to them. They’re not happy enough to reach it, but they’re at least happy enough to want it. I suspect this understanding is related to the subtle omnipresence of twelve-step methods in clinical addiction care (which I worry more broadly takes the principles and hermeneutics of a decentralized endeavor originally by and for addicts and applies them in a context where there are incentives and power dynamics not present in addict sobriety communities). The public interpretation of the relevance of twelve-step recovery seems to be that it’s not enough to just not be using: you have to become different, address the “root causes” that led you to use in the first place. The justification for soul-searching interventions isn’t necessarily that you’ll otherwise relapse. That would make little empirical sense in the face of the growing literature on spontaneous remission. It’s rather that your addictive behaviors are a manifestation of something deeper, spookier, metaphysically irreducible: past experiences, patterns of thinking, ways of interacting with the world. It’s the cognitive model of mental illness on stilts.

Even Johns Hopkins—one of the few American hospitals whose transplant center does not have a six-month rule—requires liver transplant candidates to have “insight into their own alcoholism.” The surgical director’s explanation of why coheres well with my explanation: “This is for people for whom there is evidence of an ability to turn their life around…Before we agree to the transplant, we look at the patient’s family or other support systems and the patient’s commitment to change.” The close association of “recovery” with “turning one’s life around” betrays that the addicts who are worth helping (in this case, with transplants) are the ones who self-examine and transform. That isn’t about drug use, really. It’s about changing your relationship to the world.

Medical double standards and addicts as a Rorschach test

I’ve discussed at length above the literature on alcoholics’ access to liver transplants. That conveys at first glance that the ways in which addicts are subjugated in medical care are uniform: rejection from interventions meant to offset medical consequences of their addiction, on the basis that they are addicts. But in reality, the medical resource gap is much more multifaceted than that. One addict might be precluded from transplant access on the basis of a history of alcoholism. Another could be rejected on the grounds of failure to comply with a six-month rule. Still another might be clinically required to continue substance use despite a desire to stop. (I’ll talk about that later.) Addicts’ relationship to medical care often cuts in strange opposite directions, incentivizing both use and remission. But just as the existence of affirmative action programs doesn’t mean racialized people aren’t oppressed, the apparent inconsistencies here don’t mean that the pattern doesn’t exist. It just means it’s complicated. Addicts are subjugated on the basis of current use, and of current remission, and of histories of use, and of seeming oddities in our patterns of use and remission over time. These aren’t mutually contradictory.

Bait-and-switches in clinical care

Andrew Joseph of STAT relays the case of Bryan, a young man diagnosed with opioid use disorder and cystic fibrosis who sought treatment through Mass General. The addiction team there prescribed Suboxone (an opioid agonist often used in MAT) as a long-term medication for his OUD. But when Bryan needed a lung transplant for cystic fibrosis, he was rejected from candidacy because of the Suboxone—by the transplant team at the very same hospital that had prescribed it to him.

Bryan sued and won. But when more general instantiations of addict medical oppression by bait-and-switch occur, that seldom happens. A 2022 paper by Schiff et al. uses the phrase “double bind” outright when describing the situation of pregnant opioid addicts. The authors interviewed 26 postpartum women, many of whom described being coerced into MAT by their physicians despite expressing concern that their babies would have withdrawal symptoms at birth. One reported that a nurse at her delivery “was saying that the baby was withdrawing because of me.” A second, put on MAT by one clinician, was pressured to terminate her pregnancy by another. She quotes a health care professional as saying the following:

“I noticed you were on methadone. You realize that’s liquid heroin, correct? [A]re you sure you even wanna have this baby?…I’m here to tell you, honey, it’s not easy…and [it’s really] selfish to bring a child in the world when you’re not ready…You know, as of two years ago, Massachusetts passed a law where you could be up to five months to have an abortion.”

The pregnant addicts thus felt “punished for using the recommended treatment that they had only accepted because clinicians insisted it was the right thing to do”: in some cases, by other clinicians!

More salient to the double bind is that Massachusetts makes it mandatory to report child abuse to the DCF for any pregnant person on medication management for OUD, which many of the women surveyed by Schiff et al. were not made aware of in advance of delivery. “Not one time did they tell me that DCF would be involved after my pregnancy,” said one. “If I would have known that I was gonna get in trouble for takin’ a medication that’s supposed to help me, I would have never did it.” The mothers in the study also “felt surveilled by residential programs and child protective services agencies who commonly blamed medications for…postpartum exhaustion”: again, their clinicians pressured them into a medication plan that then placed them under scrutiny by the state.

This holds for Mad people (and those wrongly diagnosed with mental illness) in general. Doctors view the wage of parental Madness or addiction as the worst possible fate for a child. According to a woman writing for the Akathisia Alliance blog:

When I requested to be tapered off of the SSRI before attempting to achieve pregnancy, I was told that the risks to a baby from his mother’s untreated depression were greater than any potential adverse effects of in-utero exposure to antidepressant medication…the doctor had instilled terror in me that if I did not stay on an antidepressant during pregnancy, I would be irrevocably harming my child.

This is reminiscent of my discussion of intergenerational erasure: addicts and Mad people are viewed as dispositionally, inherently bad parents.

These kinds of penalties imposed by various institutions for different treatment choices convey a picture in which “the right hand does not know what the left is doing.” They’re reminiscent of the carceral-clinical seesaw: you’re whacked from all sides. One department prescribes MAT while another department of the same hospital rules it a treatment contraindication; clinicians tell prospective parents that getting off MAT will hurt their child, while failing to inform them that Massachusetts state automatically reports pregnant MAT recipients to CPS.

Important information is withheld. Care is not integrated across multiple clinical dimensions. Standard elements of clinical care that nonaddicts expect are not part of addicts’ experience. This holds on a broad scale: A Brooklyn hospital secretly drug-tested a woman in labor (and apparently also earlier in her pregnancy) and conveyed the results to to the Administration for Child Services—years after a public outcry against NYC hospitals’ selective nonconsensual drug testing and child services reports against Black and brown patients. A drug user who believed herself to be having a fentanyl overdose was billed over $6,000 for a single urine test at a California clinic. A Florida pain clinic was fined $7.4 million for its groundless, systematic multi-thousand-dollar screening of its elderly clientele.

Different clinical standards of care for addicts foment an environment in which following policy to the letter in one situation renders them ineligible for receiving care in other situations. One narrative article describes the clinical phenomenon of helping people get on opioids, but not off them—creating aggressive taper plans insensitive to withdrawal symptoms. It’s well-established that physicians fear “being deceived” by drug-seeking patients lying about their symptoms, and this produces especially oppressive consequences under asymmetric-ignorance situations. A recent “secret shopper” study found that patients who take opioids for chronic pain were disproportionately rejected when seeking new primary care clinics if they indicated that their last physician had stopped prescribing them (versus retired). Clinicians monitor people with a history of addiction closely, looking for telltale signs of “manipulative” drug-seeking behavior.

“I can tell they are playing games by their intonation, their voice, their body language. They are saying, ‘I will talk the way you want to get the drugs I need.’ It’s all veiled in a whole body language to get the drug. Being ill is secondary.” -A medical resident from a qualitative survey on medical mistrust

Drug tests, screening, withholding, and coercion

To return briefly to Schiff et al.’s study, the women therein overwhelmingly felt “forced to stay on medications that they did not want or wanted to try to taper and discontinue.” One representative self-report:

“[I told] my doctor that I felt fine [yet they said] I had to be on some kind of medication to prevent relapse. They still pressured me and put it in my head like it was the best decision or whatever…I was forced. I feel like I was forced.”

But, as I mentioned above, addicts are also in many circumstances prevented from access to medication. A 2014 article by Cheatle et al. on treating pain in addict patients includes as an illustrative case history a middle-aged woman with back and leg pain whose apparent cocaine use is detected through a “routine” urine test. The patient, however, “denies cocaine use” and wants access to opioid medication for her pain. Her physician “required a consultation with an addiction specialist and arranged an appointment,” which, “on 3 occasions,” the patient failed to keep. While the authors admit that many medications can produce a false positive cocaine test, they conclude that by failing to attend the referred consultation, the patient has become noncompliant and “should not be prescribed any controlled medications until she has completed an evaluation.” They then add: “A prescription for opioids with a rapid weaning schedule can be provided to minimize withdrawal symptoms.” (“Rapid weaning” also might backfire horribly, mightn’t it?)

This person isn’t even clearly established as an addict, so imagine what it’s like if you are. I’ve already mentioned, and discussed further elsewhere, the operation of drug tests as a mode of bear-trap oppression. Drug testing is regarded as a central element of the standard of care across medical literature relating not only to substance use disorder (“Although meta-analyses did not show a significant impact of post-transplant alcohol consumption on transplant-related outcomes, authors have consistently recommended monitoring for alcohol consumption across all organ transplant patients,” writes a review article) but almost anything. For example—in keeping with the discussion of pregnant addicts—the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a committee opinion in 2017 that “screening for substance use should be a part of comprehensive obstetric care.”

The seeping of any and all substance use into the locus of inquiry of medical treatment has produced a culture on which correlations between addiction status and health outcomes are accepted, and counterevidence dismissed, without criticism—because they just seem intuitively obvious. Surely addicts are less healthy in terms of every possible metric! But you can’t separate this from preexisting attitudes toward us, and oppressions we face. Even given the way the world is, the conclusions aren’t clear; for instance, there are widely disparate interpretations of the relationship between cannabis use and various indicators of cancer patients’ health.

Upshot

I used to moonlight volunteering in data analysis for biostatistical studies. All the different patient health variables were delineated with abbreviated variables. The shorthand “hx_alcoh” meant history of alcohol abuse. That’s the only variable name I still remember because I saw it every single time I ran a risk factor query in R. It was ineliminable. The variable hx_alcoh was always the single most significant predictor—dramatic effect size, teeny-tiny p-value—of all the bad stuff. At the time I took it at face value. But even the most beautifully designed RCT on the planet cannot divide out all the differences between alcoholic and nonalcoholic people that study designers would like to think, because, as I keep saying, much of what it means to be an alcoholic is not about actually drinking alcohol. You cannot control for this with balancing scores when hx_alcoh = 1 means you’re an alcoholic and hx_alcoh = 0 means you’re not. You can control for things that travel with alcoholism, like homelessness and poverty and heart disease. But you can’t control for things that are part of my definition of alcoholism, like “being considered drug-seeking by a clinician.” They travel too tightly with this theoretically isolable predicate “addict,” and anyway the doctor obviously isn’t going to write in the notes “I am giving worse care to this patient than the last one I saw because they are an addict, in ways I don’t even realize I’m doing.” Of course, I distinguish between “addicts” on the one hand and “otherwise-similar nonaddicts” on the other all the time when arguing points. I don’t mean that this can’t be done. I just mean that it is totally consistent with much extant clinical research that addicts and otherwise-similar nonaddicts are a lot more alike with regard to features we discuss overmuch—and a lot more different in ways we don’t discuss enough—than is typically thought.

The double binds discussed in the previous sections, and the compulsory drug testing briefly described here, circle a general theme: Individual addicts, in clinical settings, become Rorschach tests for clinicians. People are going to see what they want to see, or in some way are compelled to see by auxiliary information that doesn’t really relate to the person in front of them. It’s subjective in personality-revealing ways: do you favor harms reduction, or are you pro-abstinence? Do institutionalization rates correlate negatively with crime rates because Mad people are disproportionately killers or disproportionately homicide victims (or, as I’d suggest, just marginalized)?

This is, obviously, a more general phenomenon. Every patient is to some extent a Rorschach test for their doctor, just as every student is to some extent a Rorschach test for their teacher. But what I mean has more to do with what I elsewhere term “totalizing metaphysics of addiction” than with the Foucauldian medical gaze. Recall the mushroom-eater. Typical people give no information that abstracts to the category level. It has to be remembered that they’re just anecdotes. Examining individual atypical people, though, permits the drawing of broad inferences in support of preexisting theories.

Indeed, much of the hysteria around fentanyl relies on the DEA slogan “one pill can kill”!

This is outstanding. I am still digesting the content as the ideas have been circulating in my mind for years but I’ve never seen any writing presenting them in a clear way. Thank you. I’ll be sharing.