The Puritans Are Not Your Friends

The libertines aren't either. The culture war about substances in social spaces has never been waged by or for addicts. The only winning strategy is not to play.

In the late-1800s leadup to the 18th Amendment, an organization called the Women’s Christian Temperance Union took center stage. The WCTU’s stated purpose was to attain a “sober and pure world.” Under the leadership of its second president, Frances Willard, it quickly became the largest women’s organization in the world. Willard was famous for her revolutionarily holistic approach to social ills. Prior to her election, the WCTU had operated in a similar capacity to contemporary temperance activities—direct intervention into the lives of the individuals considered to be abusing alcohol. Willard, however, was broader-minded, and viewed the problem of alcohol as inextricable from market forces and the general pressures of modernity. Willard endorsed labor rights: higher wages and the eight-hour work day. She advocated court reform. She campaigned for women’s suffrage. She strove for international justice—for “peace on earth.”

But she also wrote, in 1890, that the wage of the “grog shop”—the wellspring of Black drunkenness—is white fear. Noting the failure of prohibition ballot measures in the South, Willard argued that Black voters were to blame:

I think we have wronged the South, though we did not mean to do so. The reason was, in part, that we had irreparably wronged ourselves by putting no safeguard on the ballot-box at the North that would sift out alien illiterates. They rule our cities to-day, the saloon their palace, and the toddy stick their sceptre. It is not fair that they should vote, nor is it fair that a plantation Negro who can neither read nor write, whose ideas are bounded by the fence of his own field and the price of his own mule, should be entrusted with the ballot. We ought to have put an educational test upon that ballot from the first. The Anglo-Saxon race will never submit to be dominated by the Negro so long as his altitude reaches no higher than the personal liberty of the saloon and the power of appreciating the amount of liquor that a dollar will buy…Better whiskey and more of it has been the rallying cry of great dark-faced mobs in the Southern localities where Local Option was snowed under by the colored vote. Temperance has no enemy like that, for it is unreasoning and unreachable. To-night it promises in a great congregation, a vote for temperance at the polls to-morrow; but to-morrow twenty-five cents changes that vote in favor of the liquor seller.

Willard suggested—like segregationists of the time—that education and literacy tests be implemented at the polls to prevent illiterate Black men from voting. Here she paints a picture of Blackness as akratic: desirous of temperance but hopelessly buffeted about by the compulsion to drink. Black Southerners, she argues, are not expedient political allies for the temperance movement, for they are undependable will-o-the-wisps. By dint of their “unreasoning” irrationality, worse are they even than outright anti-prohibitionists: “Temperance has no enemy like that.” At least the liquor sellers can be reasoned with. But these sentiments are almost liberationist when compared to some of her other writing about Black people. From the same piece:

I pity the Southerners, and I believe the great mass of them are as conscientious, and kindly-intentioned toward the colored man, as an equal number of white church members at the North. Would-be demagogues lead the colored people to destruction. Half-drunken white roughs murder them at the polls, or intimidate them so that they do not vote. But the better class of people must not be blamed for this, and a more thoroughly American population than the Christian people of the South does not exist. They have the traditions, the kindliness, the probity, the courage of our forefathers. The problem on their hands is immeasurable. The colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt. The grog shop is its centre of power. The safety of woman, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment, so that men dare not go beyond the sight of their own roof-tree.

Willard may have conceived of her commentary as providing a context for racialized violence, but in actuality it is an act of apologia. She heavily implies that when “half-drunken white roughs” murder and intimidate Black southern voters, the violence is the victims’ own fault: “The better class of people must not be blamed for this…the problem on their hands is immeasurable.” And, of course, she compares Black people to locusts and claims that they—facilitated by the liquor industry—threaten the safety of families. Note too how alcoholism itself is racialized in her account. The white murderers are only half-drunken! Why on God’s green earth would a temperance advocate mitigate the predicate of “drunken” with “half”?

In 1894, when Ida B. Wells and Frances Willard were both invited speakers at a British temperance meeting, Wells had Willard’s quotations above republished in a British newspaper on the day of Willard’s speech. Willard, wrote Wells, had “unhesitatingly slandered the entire Negro race in order to gain favor with those who are hanging, shooting, and burning Negroes alive.” The two activists carried out a public dispute for months. Newspaper clippings and online reprintings convey a fossilized portrait of pure rancor, dispatches from the violent argument between temperance advocates and Black activists.

Was Willard aware that her rhetoric downplayed and even sanctioned the lynching epidemic? I allege—as Wells argued—that she knew exactly what she was doing. Of course, it’s tricky to tell from the text; it’s unclear what purpose was served by the racialization of Willard’s account of the alcohol problem. Was she primarily a racist? Or was she seizing on a pretheoretically accepted metaphysics of race—that Black people cannot be trusted with citizenship, that they are at the mercy of the alcohol that enables their savage impulses—to induce readers, through her rhetoric, toward sympathy for the temperance movement? These two things, I think, are different. But the second is no better than the first.

I think the second is more accurate. Willard in many places aligned herself with Black activists: earlier in the same interview from which the above quotes are excerpted, she promotes attitudes commonly endorsed by her Black liberationist contemporaries. And yet when it is convenient, she borrows from Peter to pay Paul—using racist violence as rhetorical tool to support her activism. She explains the subjugation of Black people as a result of the availability of alcohol, and only superable through its excision. She characterizes Black people as inferior to a certain class of educated churchgoing whites, the demarcating criterion between the groups being alcohol use. She blames Black people’s apparent voting habits (for what it’s worth, she was totally wrong about this—the Local Option was not “snowed under by the colored vote”) on weak-willedness and lack of education. She reifies the concept of Black subservience to liquor vendors precisely because she is attempting to drum up support for temperance. Alcohol is the primitive: it exacerbates and enables the worst of society.

Willard’s family was heavily involved in the abolitionist movement. She worked closely with labor organizers and Black women, many of whom joined the WCTU. It’s unhelpful in a political sense to write her off as just another racist. I’m not defending Willard here; you’ve read this article’s title. I’m saying, rather, that it’s more politically useful—conducive toward the project of identifying Willard-like people and criticizing them—to identify the relationship between their rhetoric and their expressed political goals than to dismiss them as uncritical knee-jerk racists or older variants of the modern “white feminist,” let alone as products of their age. As I wrote above, I claim Willard knew exactly what she was doing. The appellation I’d like to give to her approach, the one I think translates to modern sensibilities, is “anti-intersectional.” Willard was a temperance reductionist: she was inclined to view all evils as uniquely downstream of the universally explanatory phenomenon of alcohol availability. At best, this eliminates the agency and specificity of marginalized groups: the harms they suffer are entirely removed from their marginalized status. At worst, it motivates redescribing them as political or relational threats rather than threatened—as shown in Willard’s rhetoric. But the single-minded temperance advocate doesn’t care about that. What she cares about is promoting her cause.

To return briefly to the “half-drunken” point I mentioned above: Willard goes out of her way to express sympathy for the white Southerners’ “problem.” Across her work, she mitigates description of the drunken acts of violence committed by white Southerners and highlights those perpetrated by Black ones. She describes the lynchers as “half” inebriated, exaggerates the threat to temperance posed by the Black vote, and frames Black men as threatening women’s safety because she is attempting to coalition-build with racists—to provide a metaphysics of the Black violence they fear, and in so doing, to make her movement attractive to them. She throws them a line, gives them an avenue of access to a radical politic that they can seize hold of without questioning their received views of race.

It is this point of which Wells is most critical. Wells—also in favor of temperance reform—wrote the following in 1891:

All things considered, our race is probably not more intemperate than other races. By reason, though, of poverty, ignorance, and consequent degradation as a mass, as are behind in general advancement. We can, therefore, less afford to equal other races in that which still further debases, degrades, and impoverishes…Hence the present treatment of the temperance question will be from a race and economic standpoint.

In Wells’s account, the “temperance question” can only be considered when race and poverty are already on the table. Of course they are relevant to it. Their intersection with alcohol cannot be explained as downstream of it.

Much has been written about the Willard/Wells dispute. (A nice historiography, sharing the pieces from which I excerpt above, is given here.) I will not rehash it at great length. I will say only two things about this historical event, which stand as general principles for modern addict activism. First: Know thy enemy. Second: Know when the enemy of thy enemy is still thy enemy.

Teetotalers and libertines

I’m going to describe something I call the “substance war.” It’s an offshoot of what people tend to call the “culture war” more generally, but unlike a lot of other offshoots, it doesn’t map onto pre-established sides and neither side is even arguably correct. The substance war is the dispute between two possible answers to the question “Should substances (and certain behaviors or mechanisms) that are currently legally controlled in various ways be more accessible; should their use be more accepted in society?” The paradigm substances are alcohol and marijuana, but of course the debate extends to opioids, stimulants (cocaine and amphetamines being the common cases), inhalants, club drugs, etc. One side says yes. The other side says no. My argument here is that addict activism—if it is to exist as a general set of principles—must recommend recognizing the substance war as an intra-nonaddict dispute in which both sides are against us.

“Are there drugs on the commune?”

This stands in contrast against much ostensibly leftist discussion of drug use. So let me make it clearer: To say we should not pick a side in the substance war might sound superficially like saying we shouldn’t pick a side in the drug war. I obviously don’t mean that. The drug war is bad, criminalization is bad, etc. Agitate against this. The substance war is fought over social attitudes about drugs, and seeks to enshrine and police our drug norms rather than our drug laws. This, I think, changes a lot. We shouldn’t be uncritically supporting the liberationists in this fight. The problem is with (accurately) treating anti-drug attitudes as encroaching regulatory mechanisms in virtue of their attempts to rule and proscribe our behavior, while failing to recognize that pro-drug attitudes are doing this as well. The spectrum of palatable drug attitudes is catastrophically asymmetric. Public figures with significant audience bases have claimed that all drugs should be banned, that we should crack down hard on users, that dealers should be executed. (An ex-mufo of mine said they should be subjected to scaphism!) The right-extremal view: Ingesting even tiny quantities of drugs is an unforgivable, repugnantly antisocial sin—perpetuated by social undesirables framed in Willardian terms. The counterbalancing ideological position would be that consuming vast enormities of drugs is good or at least okay. Of course, nobody is defending such a claim. No one (outside addict/illicit drinker advocacy groups) is arguing that the kind of alcohol use that gives you the shakes is, like, fine actually.

The weirdness here is best epitomized by the sort of drug-positive essentialism you see a lot these days in left-wing spaces: drugs are fundamentally radical, our ancestors were using them millennia ago and so too will our descendants a thousand years hence; the revolution will not be sober. The mainstays of ‘subversive’ nonaddict celebration or promotion of drug use fold easily into the anti-Puritan pro-drug sensibility: drug use must be de-stigmatized; drug use is a casual, normal, even necessary part of life; drugs can be healthy and prosocial. The problem with that rhetoric is this: For addicts, drugs are not a casual, normal part of life. I don’t mean by that to criticize addicts, but rather to highlight the not-for-us-ness of the default pro-drug sentiment. What that sort of drug liberationist is celebrating is not, in fact, addicts’ drug use. They’re talking about their own drug use. Non-addicted drug use. “Responsible” drug use. “Healthy” drug use, more habitus than habit—compatible with societal contribution, with family life, with holding a job. Such drug use is assimilable into the very institutions of supracapitalist modernity they agitate against (if only on behalf of the people Apollonian enough to actually participate in them). A genuine leftist celebration of disordered drug use—that I’d love to see. I expect I never will, though, because on this issue the most ornery anarchist becomes a normativity evangelist. Many so-called anarchists—I wrote a whole separate post on this—tiptoe no further in their criticism of puritanism than Carl Hart: saying the problem with drug addicts is that they don’t use drugs correctly, but that thankfully most people aren’t like that and the real injustice is the shoehorning of poor and racialized good citizens into the corral reserved for people whom, okay, yes, something has to be done about.

And this is why ideas like the inevitability or necessary goodness of drug use are thorny. Not because drug use is bad, not because endorsing it “enables” addicts’ bad behavior, not because we live in a Society in any of the rather banal workings-out of that principle that you’d hear from a closet puritan trying to render a post hoc justification of what is ultimately a pretheoretical moral knee jerk. Rather, it’s weird because of the cognitive dissonance involved: Most such conversations about drug positivity have already a priori circumscribed addiction. As such, the attitudes represented in those conversations aren’t representative of addicts, and the experiences being celebrated often involve things actual addicts would regard as an example or consequence of their oppression (or suffering, or their life going badly, etc.) rather than some self-aware act of subversion. Addicts’ active use can be subversive in ways nonaddicts’ use isn’t, but also—and this, I think, is a characterizing feature of being an addict—can be a manifestation of addicts’ subjugation to power structures, an exploitative production typical of the ways by which addicts are made into a particular sort of economic, medical, and disciplinary subjects. Involved institutional processes exist not just to curtail addicts’ drug use, but to intensify it as well—to shape, encourage, and monetize the characteristically erratic ways we use.

This is an abstract point, and I want to move on anyway, but a perhaps useful analogy is this: think about the difference between, on the one hand, a person’s being disabled or fat or otherwise having a marginalized sort of body, and on the other, the lack of access (to spaces, activities, benefits) that such a person will often experience when confronting normative and governmental elements. A wheelchair user’s inability to enter a non-ADA-compliant apartment building, the humiliation to which a fat person is subjected when navigating a space with chairs that can’t comfortably seat them: these are not transgressive voluntary acts of resistance on the part of the subject. They’re dispatches from the trenches, not from the battlefield. Or, consider the difference between autistic people experiencing meltdowns and their pursuing special interests. The former, I think, witnesses the social mechanisms by which autistic people are made to suffer (overstimulation, ceaseless shoehorning into neurotypical norms, withholding of accommodations, etc.); the latter, their finding joy anyway. And sure, even in these circumstances, people come up with ways of subverting their own subjection to harm and misery. They crack jokes, they educate, they flip the discomfort around on the facilitators. Still, the harm itself is not something to rejoice in. To celebrate that the situation is that way—to say it will still happen “on the commune,” as it were—is just bleak. It makes no sense to want the structural forces that produce suffering for marginalized people by castigating them for their deviation from the social normal will continue after the attainment of justice. That isn’t justice! “Become ungovernable” is an odd refrain to levy at a vignette the premise of which is someone being governed.

I come at this from an identitarian perspective, not a universalist one. There are some people for whom drug decriminalization (plus a corresponding broader social permissiveness of ‘tolerable’ drug use) would be sufficient to guarantee their satisfaction. I, and many others, are not among them. I used to think that the minimal precondition for an end-of-history society in which I could flourish is that it not contain alcohol or certain drugs—if it did, if people engaged in casual recreational use, I would end up engaging in non-casual recreational use against my own desires. (And yeah, I’m sure there are drug liberationists who’d tell you I’ve been tragically propagandized into self-hatred by some sort of twelve-step demon egregore and I need to be deprogrammed. They would not, though, post bail when the mind-freeing undertakings they encourage land me in jail.) I no longer think that’s true—it would probably be enough for drugs to be conceptualized very differently from how they are in this society. And anyway, it’s complicated. Many addicts consider this question—“do we use drugs on the commune”—a calculus of fraught and competing goals. In a world where your substances of choice isn’t everywhere, they are not marginalized in some of the paradigm ways—incarcerated, institutionalized, taken advantage of by opportunistic nonaddicts. Nobody can leverage it over you. The premier way you have been disempowered, the knife that so-called friends have twisted in your back for the whole history of you, has crumpled like Goliath. But in a world where your substance of choice isn’t anywhere, you can’t use anymore, and it’s not obvious that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks of that proposition. Lots of addicts consider their drug use to be value-positive or value-neutral in itself, or to confer extremely important auxiliary benefits, or just to be a load-bearing piece of who they are. My worry is that decriminalizing drug use and stopping the social changes there simply doesn’t alter very much about addicts’ lives. We know exactly how it plays out when we legalize a substance while retaining societal approaches to it that prioritize the interests of its nonaddict users over those of its addict users. There are more alcoholics than ever; they still live navigating a veritable Bingo board of intersectional oppression and die untimely young. Economic primitives and their carceral offshoots are waiting at the ready to replace the carceral primitives and their economic offshoots as the primary fulcrum of addict suffering. Not that the carceral primitives will concede that spot easily: anyone who has ever been in the drunk tank knows societies are plenty efficacious at criminalizing the use of a legal drug when it’s addicts using it.

I brought up this “sobriety on the commune” topic only because the contemporary nonaddict anarchist view of drug politics is, to my thinking, reductive, and it is important to point out that a drug politic favorable to addicts must make demands beyond drug liberationism. So, yes, some addicts would want an ideal society to restrict or eliminate their access to their drugs of choice. But I don’t intend for my treatment of this (dilatory, obvious) consideration to tacitly pay obeisance to the reflexive belief that this topic is fraught or challenging, that the respective interests of using and non-using addicts must be balanced against each other with care. Maybe the coordination of the two groups in the here and now is difficult (although even that I’m skeptical of), but the fullness-of-time answer is obvious: Commune A for people who want to use, Commune B for people who don’t. Various desired degrees of access can all be realized in distinct physical centers with free and informed movement between them. (And there really is no reason to lose sleep trying to think of ways that could go wrong.) As for the now, at the very least I suggest as a program for addict activism that we take as central two goals, often incorrectly regarded as incompatible: decriminalization and decentralization. Make pursuit of substances not carry the wage of bear-trap oppression; also make it substantially easier for addicts aspiring to remission to avoid seeing their substance of choice everywhere and having it pushed on them in social contexts.

But anyway: Many addicts would like for their substance of choice and their thoughts about it to disappear, as if the substance itself as a cultural concept never existed. That facially seems to align with a pro-temperance view. What I argue here is that in reality, it doesn’t: both sides are against us. Here the Willard/Wells dispute is instructive in regards to the present-day substance war. Many modern nonaddicts share addict goals, or at least appear to. They want to knock drugs and alcohol from the pedestal of social centrality they occupy in our paradigm. So they initially appear to be favorable bedfellows. They say things like:

“Alcohol and drugs are unhealthy.”

“It’s terrible that these days alcohol is everywhere—you really can’t avoid it.”

These statements need to be parsed through awareness of how pro-temperance sentiments manifest and what they commit their proponents to. What is clear from the Willard/Wells debate is that the motivations of temperance advocates are different from those of the communities that seek liberation. They preach what Willard might have called “the Christian life,” and what modern temperance advocates call clean living, the purest instantiation of Foucauldian biopower. They say: substances are mind- and body-altering, and the mind and body are gifts that should not be sullied.

Nonaddict temperance advocates are not really waging a war against addicts in particular. Or at least they don’t conceptualize themselves as so doing. Their stated enemy is a totally different group: a community I’ll call the Libertines.

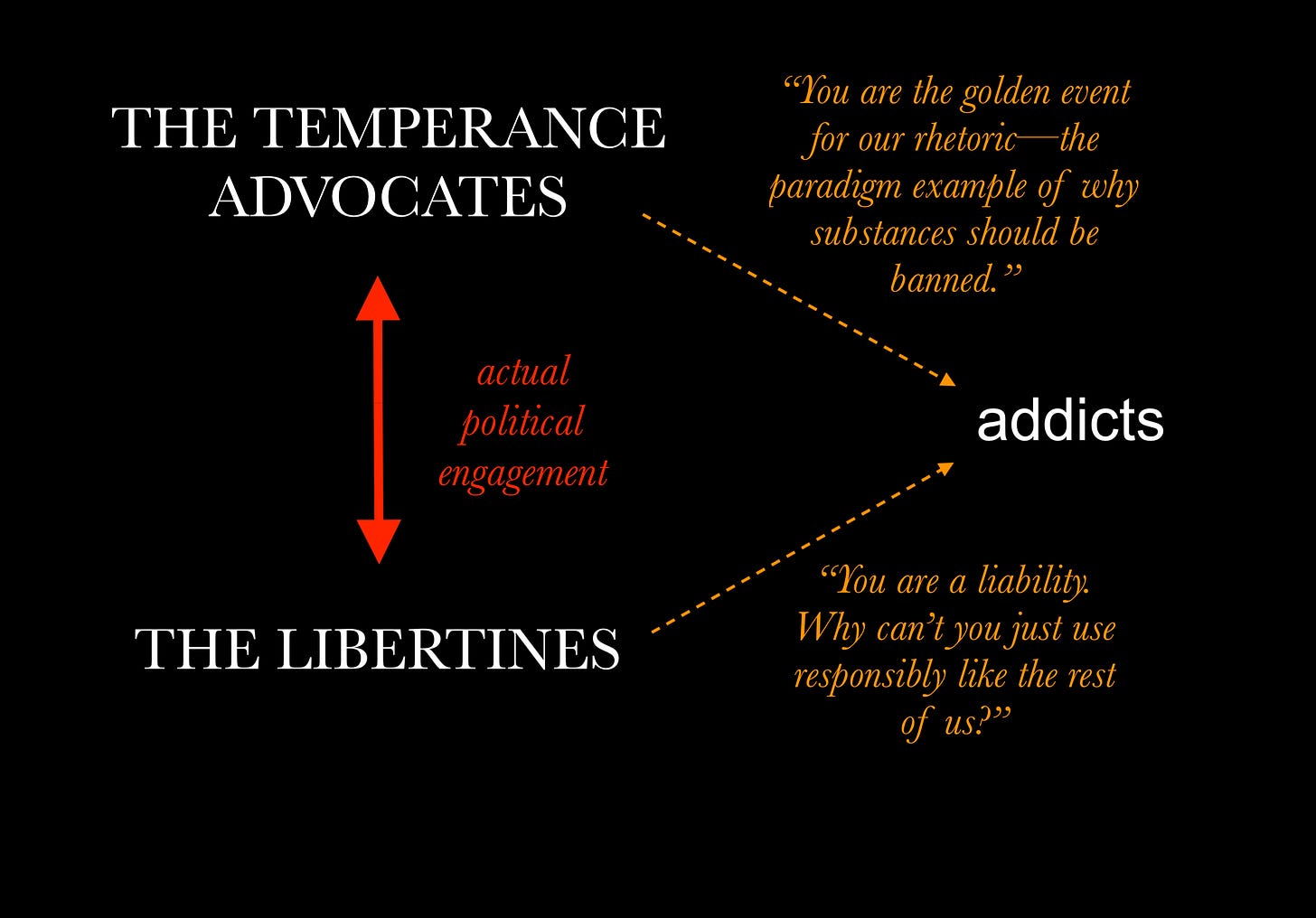

Here’s the map that lives in my head of how this debate plays out.

On the one side are the temperance advocates. They go by a variety of other names: teetotalers, or, as I’ll call them here, puritans. They seek the removal of drugs and alcohol (sometimes also gambling and various other perceived “social diseases”) from society. They are motivated towards a sort of eudaimonistic impulse: the Good Life. (That sounds underdeterministic—doesn’t everyone strive for the good life? But I mean it specifically. There are specific, person-independent, objective features that make a life go better or worse, at least sometimes instantiated through tangible objects like farms or flowers rather than abstract concepts like love or equality. Among the things that make your life go worse, or will or would given certain auxiliary conditions, are drugs.) The demarcating criterion that makes a person a temperance advocate, as opposed to a libertarian or the secret third possibility of “critical observer,” is the belief in one or more of the following:

Using drugs or alcohol constitutes an attempt to change one’s subjectivity in ways perversely influenced by the environment;

In particular, it is an intervention that makes one function in an unnatural way—in some other society, we wouldn’t need to do this; or

The widespread use of drugs, and especially the common phenomenon of addiction, is a direct cause or a direct result of negative forces that apply uniformly across society or in essential ways (i.e. being immoral makes you use; being disabled makes you use; generational trauma makes you use; alienation and capitalism make you use; Godlessness makes you use).

On the other side are the libertines. They’re an eclectic group, harder to pin down, but generally regarded as more progressive than the temperance advocates. Some don’t even use drugs. They just fight very hard for your right to use. Where the teetotalers appeal to concrete particulars in their definition of the good life, the libertines instead appeal to concepts: freedom, choice, autonomy. The ability to do things freely—in particular, to participate in alcohol and drug use, gambling, sex, and so on without legal interference or social condemnation—is crucial to their conception of what makes a person whose life is going well. Among those libertines who do use, they tend to mystify drugs (it often travels with an uncanny Western Oriental fetishism or a strong desire to have a “spirit quest”). They tend to think at least one of the following:

Drug use has always existed and will always exist; both carceral interventions and efforts to change social attitudes toward drugs are fundamentally ineffective;

Drug use doesn’t make people worse off, at least not context-independently; or

Drug use provides an avenue of access to important elements of the human experience inaccessible through other means.

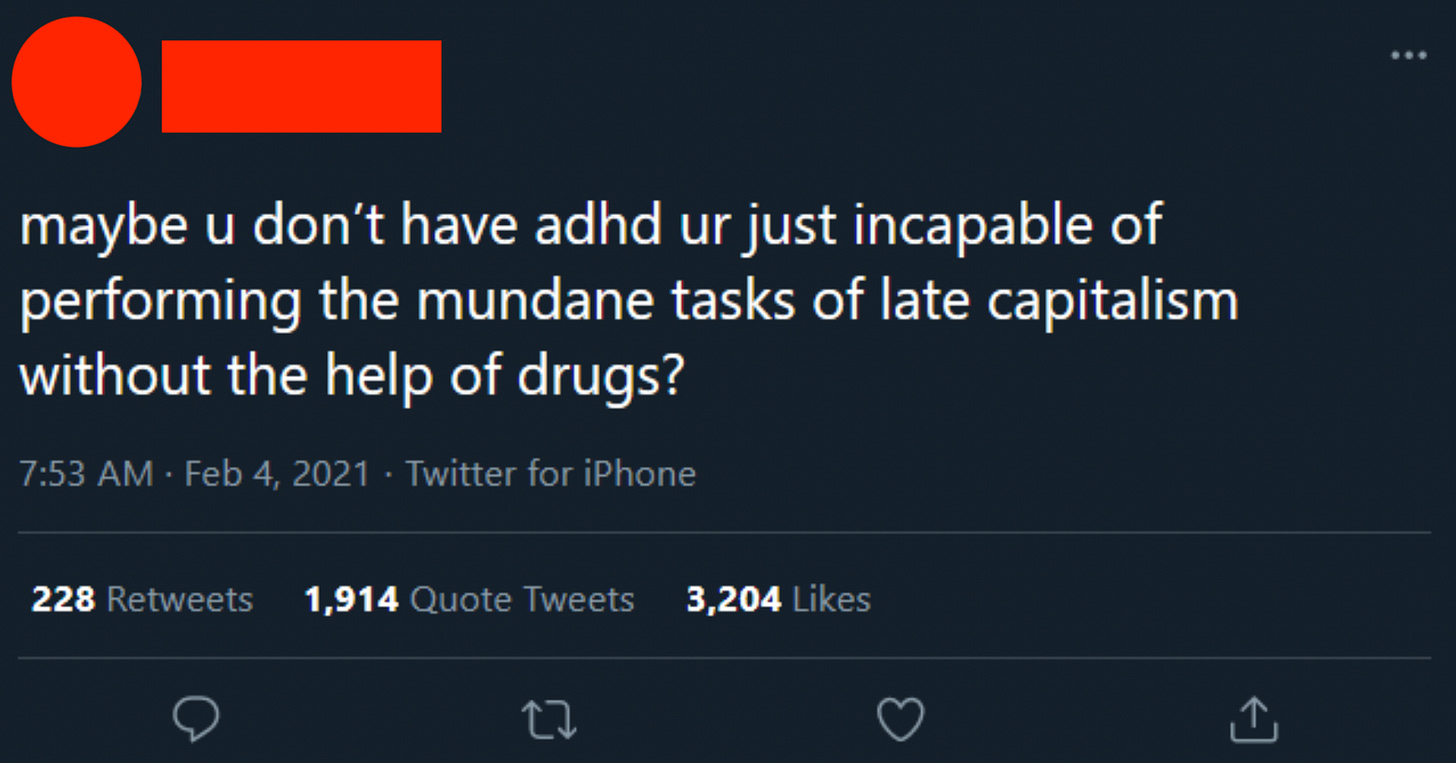

Other than the things I describe above, the partition doesn’t track much. Positionality in the puritan/libertine dichotomy does not travel with politics in an immediately tractable way. It’s a diagonal split. Puritans tend to be religious, but they need not be. Many are conservative, style themselves authoritarians, and appeal to integralist politics or some such. There are ancoms there too. For example, people like this—those who identify drug use as a coping mechanism for capitalism—are very common:

This case serves to show the non-uniformity of the position in the substance war that I call “puritanism” or “temperance.” One can’t infer from this statement that the person here thinks drug use is irreparably value-negative given the current social context, or that the people who use drugs are morally worse than those who don’t. What is clear is that they identify drug use as an attempt to get one’s body and mind to function in an unnatural way. We wouldn’t have to do that on the commune.

Libertines tend to be libertarian in a cultural sense. Some are capital-L Libertarian, but others are so-called “left-libertarians.” Still others are bona fide leftists who advocate decarceralism and think drug use is value-neutral. They think Tenderloin Centers should be everywhere. Some are accelerationists who await the world in which AGI runs everything and we all have a grand old time drugged out of our minds. (In case it’s not obvious from my flippant tone, there are few premises more self-evident to me than the fact that the image just described is not the good life.)

A three-sided war

Neither the puritans nor the libertines are allies to addicts. They’re focused upon each other; to the extent that we occur to them at all, it is as instantiations of the social ills they describe, or as edge cases and liabilities to their cause.

Nonaddict temperance advocates do not cry out against oppression. They cry out against libertinism, and their metaphysics is inseparable from the Protestant-work-ethic received view that particular kinds of authentic social function ennoble. They view substance users as decadent degenerates and are in turn viewed by them as prudish harpies. The tug-of-war is between morality and autonomy. Teetotalers are good; libertines are free. This frames the debate firmly within the space of neoliberal values; it makes suffering a collective goods problem.

I pick no sides here. They’re both wrong, and anyways addicts have no place in the libertine-puritan dialectic. I have no incentive to break up this fistfight between strangers. It is a dispute carried out along an irrelevant axis, orthogonal to our project. Harms reduction interventions do not make sense if the process by which harms are caused is not disrupted by the intervention. Much like a decarceralist watching two shades of liberal haggle about police funding, I observe this battle with a mixture of bafflement and annoyance. Bafflement: it’s simply the wrong issue. What do I care? Annoyance: Both sides view addicts primarily and finally as a token. For the libertines, we are an edge case that needs to be carefully separated from the nonaddicts lest we ruin drugs for the rest of them.

Among the “many paths to divinity” are being able to handle yourself and being constitutionally unable to, apparently.

To the puritans, we are a public menace.

“Degeneracy on the streets”—a spectacle to be eradicated—is the role of addicts in the puritan narrative.

Sometimes, in the libertine/puritan debate, other prejudices come to the surface in ways we should consider instructive.

This reply, as collateral damage, legislates alcoholics as uniformly unsuccessful.

This last account self-describes as a National Socialist.

The enemy of your enemy is not always your friend. Obviously, if they’re Nazis who call women who drink “roast beef stragglers” and drinkers at large “fucking stupid,” then you cannot build a coalition with them. But the point holds more generally.

The people who think drinking and drug use are indefensible social evils—that they make you not necessarily a worse person, but worse at being a person—are not our friends. They do not wish to protect us from societal oppression. They want, rather, to protect society from us. Remember Willard’s words: “The safety of woman, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment.” We, the addicts, are the enemy. They will demonize us, slander us, incarcerate us, and take our children, and they will conceive of themselves as virtuous for it. These are not groundless predictions; these are empirical facts. (Prior to the passage of ICWA, up to 35% of Indigenous children were trafficked into Indian schools and orphanages and non-Indigenous households on spurious grounds of parental substance use.)

Nonaddict temperance advocates view addicts—poor and racialized addicts in particular—as menaces to the safety and functioning of society. Their stories are of broken homes and shattered lives, but they themselves are always portrayed as hapless collateral damage of the separable, free-standing catastrophe of someone else’s addiction. Their battle cry is individualization at its finest: “Some people can’t drink or use responsibly, and those people ruin it for the rest of us.” At best we are defective persons to them; at worst we are opportunistic instantiations of evil.

Addict activism should define itself in opposition to both these camps, because it is for, by, and about us. We will not be used as rhetorical demons, nor brushed under the rug as embarrassments to the cause.

Willard’s key mistake was believing that the extent to which she agreed with racists (that there was alcohol-exacerbated racial unrest in the South) justified conciliation to their terms. That will never be true. She and the racists she aligned herself with are not your friends. But—this is harder but no less important—neither are the libertarians who think addicts are awkward impediments to the narrative that people should generally be allowed to use drugs freely. While we pursue both goals at once, to decriminalize and decentralize, we must do so in ways far removed from the nonaddict standpoint. We must treat the current face of the substance war just as it treats us: as an irrelevancy.