Addict oppression: the carceral-clinical seesaw

Institutions and prisons play Whack-A-Mole with addicts.

Introduction to this series

In the About page for this blog, and in some posts, we’ve discussed the concept of addict oppression: the idea that addicts are marginalized at least partly in virtue of being addicts. In this series, I want to elaborate on that. I’ll describe the ways in which addict oppression manifests, replying to some objections, and clarifying the finer points. My purpose here is to characterize the mechanisms of addict oppression, and motivate the definition of “addict” as the set of people it targets.

My claim is that addicts are subjected to various forms of penalty, marginalization, sanction, and harm in virtue of being addicts. These most canonically operate as punishments for behaviors, but can also manifest as almost-automatic responses to dispositions or disclosures. Sometimes addict oppression involves punishment for substance use: being arrested for possession, charged with public intoxication, subjected to drug tests. Sometimes it’s punishment for not using: being refused aid when navigating withdrawal symptoms, excluded or not provided accommodations in situations where our substance of choice is present. And—though this might sound bizarre—sometimes addicts are punished for both, for the seeming atypicality of their substance use patterns. Resources and interventions are withheld on the grounds that since addicts apparently sometimes exert control over consumption, you could stop if you really wanted to. Finally, addicts are oppressed just for being considered addicts in the first place, in ways independent of current use patterns. Addicts’ history of addiction is used against them. They’re considered drug-seeking in clinical settings, or face barriers to family reunification. They are considered untrustworthy when providing testimony—not just about addiction, but about anything. They are evaluated as manipulative: “Never trust an addict.”

In what follows, I’ll lay out some of the most common modes of addict oppression. I organize them into four subcategories: the carceral-clinical seesaw, intergenerational erasure, the resource gap, and economic exploitation. This is not necessarily exhaustive, but I think it’s representative. The first three, I think, are notably salient in Mad oppression more generally. (The last is kind of idiosyncratic.) I’ll tackle one of the four in each of four posts, then address some objections or sources of confusion in still another post.

The carceral-clinical seesaw

Content warning for this section: suicide and overdose.

Prisons and incarceration

The residents of jails and prisons in the United States, Canada, and Mexico are disproportionately—in fact, overwhelmingly—alcohol and drug addicts. For the U.S., estimates range from 60% to 80%. (Gambling addicts are also dramatically overrepresented among arrestees.) Addiction recovery specialists have argued that mass incarceration is the United States’s mechanism for handling addiction crises. Indeed, arrests for possession and manufacture outright number at around one million each year, and drug abuse violations, DUIs, and drunkenness are among the most common causes for arrest.

A crucial vessel in the incarceration paradigm of addict oppression is the criminalization of substance possession, and in particular the existence of mandatory minimum sentences. This is a relatively recent historical development. After the onset of the crack epidemic and the death of Len Bias, the Anti Drug Abuse Act passed both houses of Congress in November 1986, facilitating much greater carceral vigilance concerning drug use. A 1995 Villanova Law Review article opens with tragic anecdotes of young first-time offenders sentenced to 10-year or higher mandatory minimums for minor roles in facilitating others’ drug access—Paulita Cadiz and Johnny Patillo—and examines in depth the case of Ronald Harmelin, a first-time offender who was sentenced to life in prison without parole in accordance with the mandatory minimum statute for possession of a large quantity of cocaine. Harmelin's lawyers challenged the sentence on Eighth Amendment grounds; the case went to the Supreme Court and divided the judges. The majority opinion, authored by Scalia, upheld the sentence. (The Michigan state legislature later revoked the 650-lifer law, retroactively overturning Harmelin’s sentence.) Minimums remain extremely asymmetric across substances; much has been written about the 100-to-1 ratio between the minimum quantities for 5-year sentences for crack and powder cocaine. The disparity was reduced under the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 to 18-to-1 and remains there.

It is usually argued in response to these claims that people convicted of simple possession make up only a small proportion of incarcerated people. True! Possession charges are not the only or even the most common vehicle by which addicts are carcerally oppressed. But addiction is the unifying feature of North America’s prison population. Addicts are a category of person that overlaps in a non-coincidental way with the category of incarcerated persons.

There’s a tendency to respond to information like this—about the overrepresentation of addiction, racialization, Madness, and poverty in the prison population—with “Yeah, well, those are just the people doing the crime.” It’s an especially salient reaction given that addicts’ carceralization in particular interacts in seemingly non-accidental ways with participating in and facilitating drug use. According to a Bureau of Justice report from 2017, 21% of the people then-incarcerated in state prisons and jails were sentenced for crimes committed for the purpose of obtaining drugs or money for drugs. 40% of incarcerated people were using drugs at the time of their criminal offense. (For juvenile justice facilities, this number balloons to around 80%.) To interpret such statistics uncritically forwards the narratives that addicts have criminal motives nonaddicts don’t, and that altered subjectivities more conducive to dangerous behavior. In my clarificatory post later, I’ll address at length how the stigma-not-oppression mindset plays right into this: “Addicts aren’t born as dispositionally dangerous people; uncontrolled drug use just makes them that way.”

This approach carries water for carceralism. It’s in no sense sympathetic to addict liberation. But anyway: The “these are just the criminals, I guess” explanation is just not correct. It’s been effectively deconstructed by decarceralist authors when levied to explain the disproportionate racialization of convicts and inmates. Michelle Alexander has written on the cycle of incarceration for poor Black men, and something similar happens here. Addicts are the people who find themselves in desperate straits. The system is self-reinforcing: addicts, already profiled, stereotyped, and entrapped, are then made vulnerable by the cycle of arrest and release motivating their return to active use and engagement with criminal structures. Elsewhere I describe how marginalization works by shibboleths, and lay out the concept of bear-trap oppression. That’s what’s happening here. Addicts are policed for their drug use at much greater rates than nonaddicts who also use drugs, in ways not entirely reducible to the differing consequences of those two groups’ drug use. Their participation in illegal behavior is incentivized through perverse systems that many nonaddicts do not ever encounter. Addicts have a much higher likelihood of coming into contact with the carceral apparatus in the first place, and the system is conducive to recidivism for a variety of reasons well-characterized elsewhere.

Institutionalization

There’s another way addicts are subjected to repeated confinement: institutionalization. Currently, 37 U.S. states and D.C. permit legal involuntary institutionalization of addicts. Writes the National Judicial Opioid Task Force: “Involuntary commitment laws, while not a panacea, are one tool to help address SUDs.” These laws, known as civil commitment (CC) states, are widely regarded as unproblematic and effective by health care providers. A 2021 issue of the Journal of Addiction Medicine contains a national survey of members of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, finding that of the 165 physicians who submitted the survey, 60.7% were in favor of CC and only 21.5% opposed. Additionally, the level of familiarity with CC was low: over a third of the respondents were “unfamiliar” and 28.8% did not know whether civil commitment for substance use disorder was legal in their state. (A companion article expressed concern at this result.)

The two work together

Incarceration and institutionalization aren’t isolated, non-interacting structures exerting dominance over addicts’ lives. Addicts—like Mad people1—often spend their lives ping-ponging between emergency wards, rehabs, and jails, getting out of one only to be placed in another. I call this the carceral-clinical seesaw.

Imagine that the recidivism cycle of incarceration is like an arcade house Whack-A-Mole game: every time you pop out, the powers that be smack you back into confinement. The carceral-clinical seesaw is like a two-sided Whack-A-Mole machine where there are players whacking on both the top and the underside of the board. When you dip below the sight line of one, you emerge into the perceptual field of the other, to be whacked in the opposite direction.

The criminal justice system subjects you to one set of penalties. The sanatorial system waits its turn and then subjects you to another. Experientially, this can produce the illusion that the two structures are fighting with each other for the right to confine you: that one side wants you incarcerated and the other wants you committed. But in actuality, the carceral and clinical apparatuses are cooperating. Their concurrent operation neutralizes addicts. It doesn’t really matter which deals the death blow.

The carceral-clinical seesaw manifests through the variety of mechanisms in which addicts are offered apparent choice between the modes of institutionalization, or sent to one type of facility for norms violations intuitively under the scope of the other, or shuffled between the two. For instance: judges and legal bodies often sentence addicts to court-ordered inpatient treatment or rehab, rewarding attendance with reduced prison or jail time and punishing attrition with harsher penalties. Drug courts involve hybridized carceral and rehabilitative mechanisms that intertwine: “noncompliance” carries the wage of fines, mandatory work, and reincarceration. Intake screenings subject prison inmates to the concern of the clinical apparatus, the attention of which they might not have otherwise received. Moreover, being imprisoned causes people substantive psychological harm—it’s been directly linked to depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

But the reverse causal direction also holds: the clinical apparatus facilitates and justifies carceral subjugation. American states have a long history of incarcerating people who haven’t been charged with anything but are awaiting psychiatric evaluation. People charged and suspected “not competent” to stand trial can languish in jail for the same reason. Others who are charged, but not convicted, can be civilly committed (especially if the alleged crime is sexual). In the U.S. Virgin Islands, people found not guilty by reason of mental disease or defect are just kept in jail.

In Massachusetts, addicts can be civilly committed to a treatment facility in a prison despite not being charged with anything. A representative case is that of Sean Wallace, a heroin addict who was involuntarily committed to a state prison in Plymouth. Wallace was denied MAT and subjected to abuse—placed in “the hole” as punishment for not eating. He committed suicide shortly after his release.

This is extremely common—in fact, people who have been institutionalized are more likely to commit suicide immediately after release than at any other time in their lives. This shouldn’t be shocking: the conditions in institutional facilities are often “horrific,” including “squalid conditions and patient neglect.” Important to the carceral-clinical seesaw is the fact that many institutional facilities are indistinguishable from prisons (indeed, institutionalized people often have fewer privileges than incarcerated people). In a 1999 study of 10,000 recent suicides in England and Wales, 3,270 had “had contact with mental health services in the year before death.” Virtually all were Mad or addicts—mostly alcoholics, schizophrenics, bipolar, depressed, or diagnosed with a PD. 26% were “noncompliant with drug treatment.” The majority of the deaths occurred in the first three months after discharge, but 16% were in inpatient treatment at the time of their suicide. Among these, most had been recently admitted. A 2010 editorial reports that “paradoxically, both admissions to a psychiatric ward and recent discharge from it have been found to increase risk for suicidal behaviours.” These facts have motivated clinicians to adopt protocols for closely monitoring newly admitted patients, but up to 9% of inpatient suicides occur under constant monitoring.

Addicts recently released from prison are also disproportionately likely to die—by overdose. (In fact, the leading cause of death internationally among people recently released from incarceration is opioid overdose.) One recipient of addiction treatment with a history of incarceration reported that ten of his friends overdosed shortly after their release. The mechanism is the inaccessibility of substances in prison—addicts frequently turn to suboxone, or other less potent replacements, in order to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Once released, they return to their substance of choice: “Your tolerance is so low, you can’t take as much. You get out and, bam, next thing you know you're dead.” Or hospitalized, back on the clinical side—out of the frying pan, into the fire.

Dangerousness versus desert

The carceral-clinical seesaw is inseparable from the way the public at large thinks about addicts and Mad people. While addict incarceration transformed as a result of the crack panic, the underlying impetus isn’t new. Henninger and Sung’s entry in the Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice paints a brief history of the political and medical mechanisms: in the early 1900s, addicts (primarily to alcohol, opioid, and cocaine) were sent to “mandatory detention” in psychiatric centers or treatment "colonies." After the passage of the Harrison Act at the end of 1914, the number of addicts in jails and prisons increased exponentially. The overcrowding of penitentiaries motivated the creation of federal “narcotics farms” (2261). Already the early twentieth century saw these people shuffled between carceral and clinical detention by a government that did not really know, and still today doesn’t know, what to do with them.

This brings me to the single most important point I want to make in this entire post, which is the psychology underlying the carceral-clinical seesaw. Why does this double-sided Whack-A-Mole machine exist? It’s facilitated by the general sensibility that a preconceived segment of the population (addicts and Mad people) is dispositionally dangerous. Such people are stochastic variables, subject to explosion at any time. Hence they need to be kept away from other people. The details of how that works aren’t important; it doesn’t matter if their sequestration is carried out via incarceration, institutionalization, or death. That’s because the vindication of this model for the treatment of addicts and Mad people is neither retributivist nor rehabilitative. It’s pragmatist. It’s not about people’s needing to be punished or changed; it’s about their needing to be eliminated. Sure, historically incarceration has been justified by appeal to moral desert. But that isn’t the case anymore, not for addicts anyway. We aren’t widely viewed—I can’t stress this enough—as blameworthy or evil, or if we are, it’s not relevant. We’re viewed as dangerous. That’s what does the justificatory work here.

Outgrowths of the carceral and sanatorial superstructures have emerged in response to the apparent insufficiency of the other arm to incapacitate this demographic, and calls for expansions in either system often make explicit reference to such inadequacies. Responses to the recent death of Mad addict Jordan Neely encapsulate this phenomenon perfectly. (Neely was killed by former Marine Daniel Penny for the ostensible crime of screaming, and maybe throwing trash at people, in a subway car. The requisite posthumous investigation of Neely’s history that media outlets love to do in these sorts of situations revealed a long history of arrest and hospitalization.) New York mayor Eric Adams used Neely’s death to push for his plan to dramatically increase involuntary institutionalization: “It is time to build a new consensus around what can and must be done for those living with serious mental illness and to take meaningful action despite resistance and pushback from those who misconstrue our intentions.”

This is in keeping with a general pattern of focus on Neely rather than his killer. Maybe it’s unsurprising that pro-broken-windows-policing news outlets blatantly attempt to paint Neely as the dangerous party in the interaction. But importantly, progressives are not immune to this. They uncritically construe any possible counterfactuals as centered on Neely—how could he have behaved differently, not conspicuously Mad?—rather than on Penny. It’s self-contradictory, really. We treat Mad people as both incapable of change and the only people in interactions between the Mad and the non-Mad who could in principle be changed, intrinsically or extrinsically. We don’t ask what Penny or the passersby could’ve done differently. We ask: What could we have done, as a society, to prevent Neely from causing trouble? It’s just assumed that his dying was an inevitable outcome of a fixed action pattern set in motion by his outburst. The received sentiment: People will always feel threatened by the Mad, and they’re right to feel that way. Awais Aftab wrote a great piece on this; here’s a relevant excerpt:

[R]eflected in Mayor Eric Adams’s statement is…the sentiment that individuals with serious mental illness should be, by whatever means necessary and for their own good, confined and excluded from public life. Why are individuals with mental illnesses on the streets and the subways? They must be protected from all situations where they could become a danger or become endangered. Put them in facilities, put them in hospitals and group homes, keep them chemically subdued, whatever, everything will be ok if we can go back to pretending in our day-to-day lives that they don’t exist, and if we don’t have to deal with them…The real dilemma we confront is that we have created societies that cannot tolerate and accommodate states of madness.

By whatever means necessary and for their own good. That’s exactly it! This narrative scratches a particular sort of itch familiar to the person who feels some doubt or self-reflection about the social practice of shunning the Mad. On the dangerousness justification, that doubt is assuaged. We’re dangerous to others, or to ourselves, or maybe in a non-person-indexed way it’s just dangerous for us to be around. People can sidestep the ethics of a programme like mass institutionalization by appealing to these broad, vague counterfactuals intimating that everything is always dramatically worse for everyone when Mad people and addicts run free on the streets. If our being in public is an unmitigated catastrophe, then almost any alternative is worth the costs. And—crucially—our being in public is so construed, not just for the sane people, but also for ourselves.

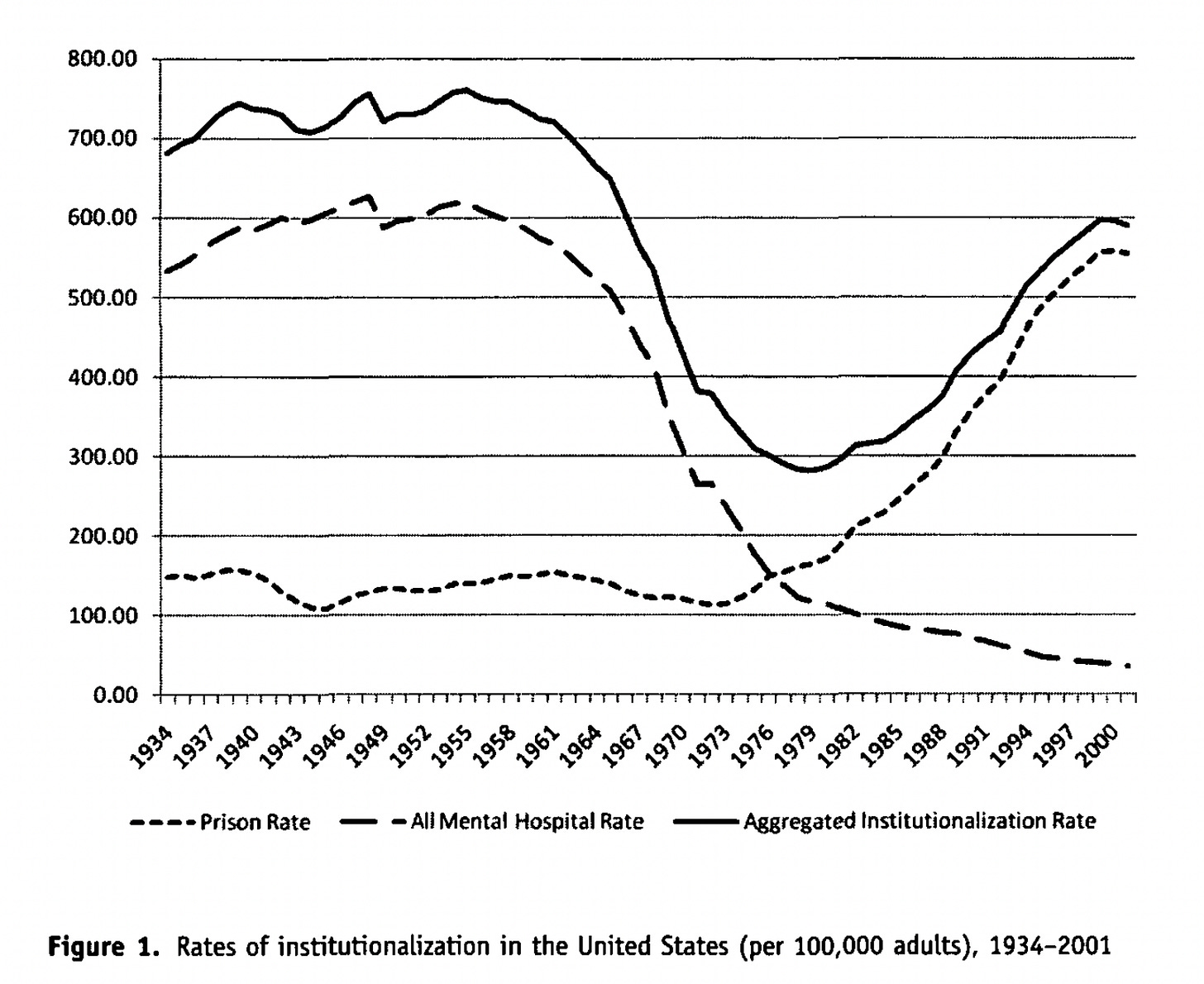

The following graph—reproduced from a 2011 paper by Bernard Harcourt—has been widely shared on social media in response to Neely’s killing:

When tough-on-crime advocates post this, what you’re meant to take away from it is obvious: as institutionalization rates go down, incarceration rates will necessarily go up because the people committing crime were institutionalized in the past and are getting incarcerated now. The dangerous people are stable in proportion, or at least cleanly able to be indexed as such. What has changed over time is how they are handled. Addicts and Mad people are the molecules in a constant-volume gas thermometer: the same in number, but exerting different rates of pressure as the social responses change.

Of course, that’s not what careful treatments show. (As one study points out: “While a historical correlation between rising inmate numbers and falling psychiatric bed numbers exists, this correlation does not necessarily imply that a potential policy that exogenously increases the number of psychiatric beds would decrease inmate numbers.”) But more to the point, it’s not even unambiguously what this graph shows! At best it shows that people who are being incarcerated would have otherwise been institutionalized, which is not the same thing. But even that weaker claim is not what Harcourt himself argues. Though he does suggest that the correlation “confirms a basic intuition, namely, that safely incapacitating portions of the population will have negative effects on crime rates” (75), he also says this:

The bottom line is straightforward: prison rates alone do not predict homicide, nor do mental hospitalization rates alone, but when the two are combined, they are significantly and robustly related to homicide rates…This study identifies a previously unnoticed empirical relationship and cautiously speculates on the mechanism. The mechanism, it turns out, may be victimization rather than perpetration. Research has consistently shown that persons suffering from mental illness are far more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general population…What may explain the results, then, is that the large institutionalized populations contain a higher proportion of potential homicide victims than the general population. The size of the institutionalized population may be relevant to homicide rates, not simply through perpetration, but through the higher victimization rates of the persons detained (44).

I don’t mean here to imply that I agree uncritically with the Mad-people-must-be-either-perpetrators-or-victims dichotomy. I’m just pointing out that it is informative how the modern discursive apparatus ignores the systematic victimization of Mad people, focusing instead on isolating their dangerousness.

People construe circumstances like Neely’s death as motivating the omnipresent Question of How We Should Handle Mentally Ill Homeless Addicts. If we just incapacitated addicts and Mad people in a more effective way, crime would go down. What’s the effective way? Let the bureaucrats argue about it, we say. In the meantime, the relevant people are unmoored back and forth by the carceral-clinical seesaw. Throughout the entirety of their short existences on earth, the determination of what happens to them is determined by this equilibrium of warring superstructures. They become objects to be passed between. Their self-determination is tossed back and forth as they watch—like two mean-spirited middle schoolers playing keep-away with a child’s inhaler.

I’m not sure where I stand on the question of whether addicts should be considered a subset of Mad people or a different group of also-disabled people whose oppression functions by very similar means through convergent evolution. Some time ago I suggested the self-descriptive term “Maddict” for the overwhelming majority of Mad people who are addicts, and vice versa. But that might be redundant!