Shibboleths of Marginalization and Category Conflation

When causal claims are spurious, often the underlying correlations are too.

Some ways of describing people are more laden than others. People don’t tend to think the predicate “current resident of Canada” tells you anything essential about the people who satisfy it. Not so for “addict,” “trans,” “autistic,” “narcissist,” “70-IQ.” These two kinds of categories (things like “Canada resident” on the one hand, and things like “70-IQ” on the other) are deployed differently. “Canada resident” just means what it says—that you reside in Canada. “70-IQ” means something stronger. It is used to convey information that has nothing to do with IQ test performance.

An ongoing focus of mine is explaining and critiquing this demarcation. So let’s look at categories of the first kind: attributions used to convey information about people over and above what they strictly mean (if indeed it can be argued that they strictly mean anything at all). I call them baggage categories, because they carry baggage. They import history, interiority, social positionality. Adding them to a sentence functions to produce an explanation, to toggle credibility, to impose a threat. Meanwhile, there are other ways to describe people that are broadly recognized as not operating in that way. These baggage-free groupings are cashed out entirely in terms of a specific, localized predicate. To be a member of the category “Guinness world record holder” means exactly that and nothing more.

For almost any two predicates you can name, you can find weird statistical relationships if you look hard enough. White people are more likely to have pets. Blind people are better at arithmetic. Canadians are still pretty tall, but not getting taller as fast as other people. Most people just shrug about this: sometimes categories overlap for no reason, or for uninteresting reasons. Ray Blanchard has papers purporting to show that gay people are disproportionately left-handed, that gay men tend to have more older brothers, lots of stuff like that—but that isn’t why you know his name.

Which is to say: it absolutely fascinates people when baggage categories overlap. If statistical relationships exist between intuitively unrelated categories that carry baggage (like addicts and bisexuals) that notion is considered independently interesting. When this happens—when correlations emerge in seemingly non-tautological ways—it motivates people to conjecture explanations, to affirm or contest preexisting causal theories. I call this phenomenon category conflation: two baggage categories travel together, for reasons that are not immediately obvious.

What I mean by “category conflation” is an empirical claim about significant correlation between predicates or distributions that is interpreted as necessarily non-accidental. Often the researchers themselves are confused by these; they seem to have come out of nowhere. People then attempt to explain the overlap in terms of salient features of the groups, or of the social conditions of their interaction. They disagree about the reason, but they agree that there must be one.

What bothers people is the feeling that disparate categorization schemas have evolved convergently. Autistic people are disproportionately trans. Addicts are disproportionately diagnosed with cluster B personality disorders.1 A metric seemingly develops a mind of its own, tracking other stuff it has no business tracking. But though these relationships are spurious, they aren’t random: our interest in category conflations is part of what makes them arise. In speculating about them, we play into them, making the correlations ever larger and more salient. So buckle in: if these kinds of associations make you itch, then you are due to be itchy a lot.

Trans people and autistic people

The recent Missouri emergency rule (here) restricting gender-affirming health interventions has prompted a back-and-forth in terms of legal enforceability.2 The rule details a laundry list of exclusion cases in which gender-affirming care is prohibited. Its clearly stated purpose is to prevent possible misdiagnosis of patients who aren’t actually trans but have been led to believe they are trans by “social contagion,” “mental health comorbidities” and “autism.”

The general interpretation of the rule’s scope is that any autistic or Mad person is prohibited carte blanche from PBT, hormone therapy, and GAS—unless and until they are no longer diagnosable. Its justification is the existence of, you guessed it, a category conflation. There is a well-established correlation between being autistic and being trans. On this much, most people seem to agree:

There is some fundamental, context-independent fact of the matter about whether autistic people are more likely to be trans (if you support trans liberation) or to “self-identify” as trans or be “gender-confused” (if you’re gender-critical).

The fact of the matter is that, yes, they are.

This is to say: People are arguing about whether autistic people, who disproportionately self-describe as trans, should have access to the slate of interventions that they (maybe insincerely, if they’re gender-critical) parse as within the scope of neurotypical people’s self-determination and choice. Some say yes, some say no. But neither side seems interested in questioning the claim that autistic people are inherently more likely to identify as trans. They disagree about whether such identification is legitimate; they explain the overlap by appeal to different auxiliary factors. The gender-critical camp will tell you that autistic children are peculiarly vulnerable to being tricked into identifying as trans. “It’s horrifying!” One psychiatrist writes that autistic people “have great difficulty letting go of something once they believe it’s true,” making them “particularly susceptible to issues with their gender identity.” On this view, the explanation for the disproportionate overlap between trans people and autistic people is that the mechanism of being led to believe you’re trans is levied at everybody but unusually successful when you’re autistic. Transness, they think, is a category imperfectly tracked by clinical metrics (or nonexistent), whereas being autistic is perfectly tracked by them. (They must think this—otherwise they wouldn’t be so sure that being autistic must be the underlying condition.)

Their opponents explain the category conflation in a way that frames the influence of autistic identity on trans identity as constructive rather than problematic. Autistic people “are familiar with operating outside of societal norms and expectations”; they are “better at clearly communicating…their identity.” Hence the overlap is explained in terms of features of being autistic and being trans: autistic people conceptualize gender in more radical ways that neurotypicals do.

I don’t think the trans liberation movement should appeal to these sorts of explanations, because they concede too much to the opposition. They agree that being autistic and being trans are context-independent kinds of interiority—genetic and essential, paving the way for born-this-way theories that have been rightly criticized by trans feminists.

Addicts and personality disorders

List all the addict television characters you can name. Here’s a few: Gregory House, BoJack Horseman, Sterling Archer, Rick from Rick and Morty. These people are all terrible. Or—to be more precise—they’re coded to parse as terrible, to make you hate them, or at least hate yourself for adoring them. They cheat, lie, steal, and insult. And throughout it all, they remain bitter but beautiful geniuses: woefully in touch with the human condition despite, or perhaps because of, their morbidity.

Few stereotypes are as profoundly accepted within our cultural hermeneutics as the idea that addicts have cluster B personality disorders. You cannot watch an hour of TV without encountering this equivalence.3 But the conflation is, at its root, clinical. Some studies report that up to 80% of addicts have comorbid PDs, averaging almost two each! Others are more conservative: “the overall prevalence of PD ranges from 10% to 14.8% in the normal population and from 34.8% to 73.0% in patients treated for addictions.” But still other researchers argue that PDs are “probably over-diagnosed” in addicts. That’s because, maybe, being an addict makes you behaviorally resemble people who’ve been diagnosed with PDs, as a convergent evolution phenomenon— “some of the criteria of personality disorders…may be the result of substance abuse.”

The debate works much the same as in the previous case. One side explains the overlap in terms of underlying qualities of the groups. The other proposes an alternate explanation: the PD-discerning mechanism goes haywire when applied to addicts. Neither contests that both addiction and personality disorders are biologically defined phenomena, the Platonic definitions of which our possibly-wrong current clinical interpretations of them are directed toward realizing.

What I argue here is that we should be critical of that! Part of the content of being an addict, or Mad, or autistic, or trans, is self-conceptualizing and being conceptualized by others that way. The whole line of inquiry that leads one to investigate why categories conflate is misguided. “Are addicts more likely than nonaddicts to be narcissists?” and “Are autistic people more likely to be trans?” are questions that do not make sense. So I’m laying out here my general, reductionist theory of why category conflations between marginalized populations happen.

An urn problem

Imagine you’re a research scientist looking at these two urns, A and B, containing balls. Currently the light is off, so all the balls appear dark in color.

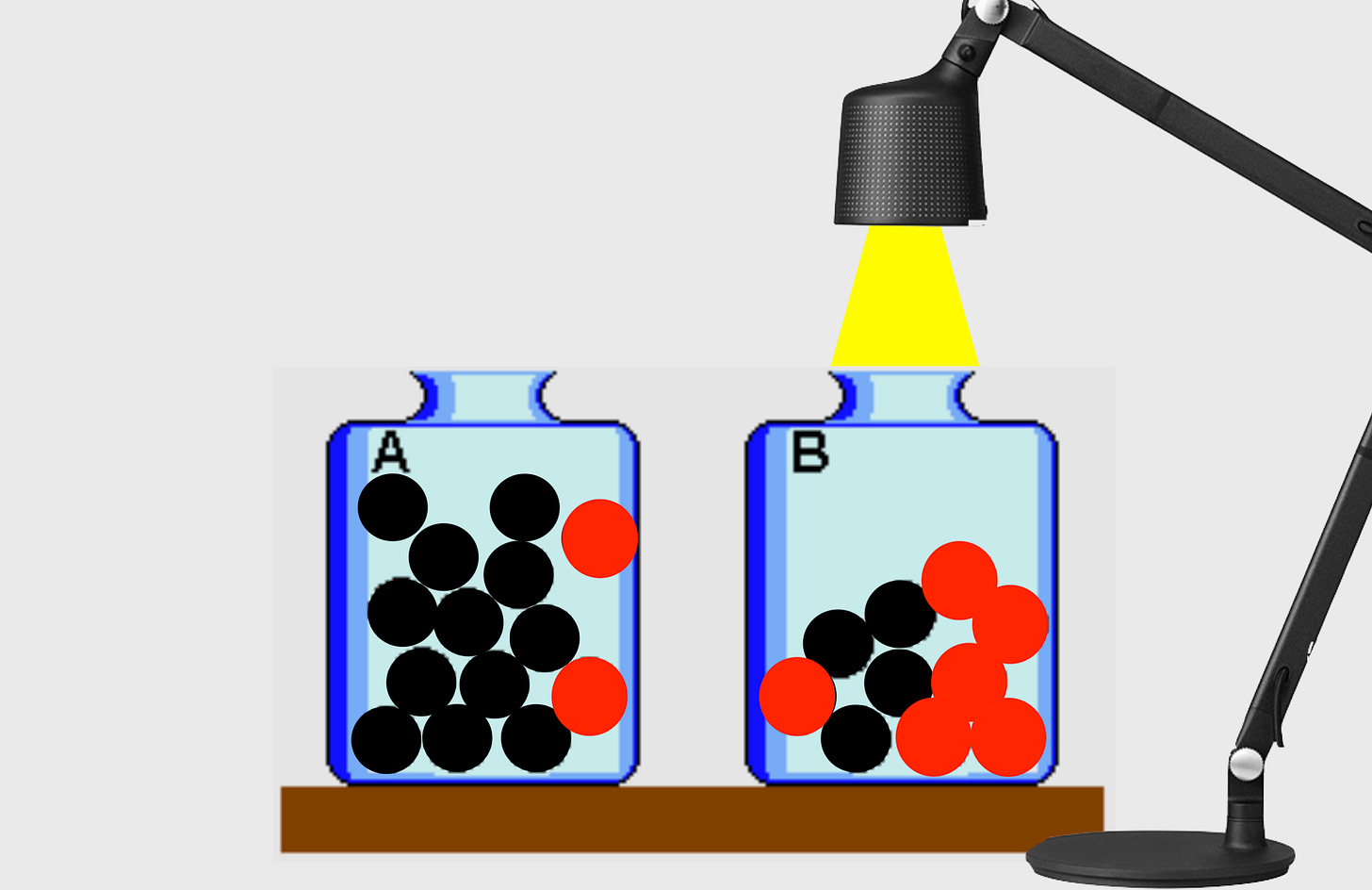

You want to know what proportion of the balls in each urn are red. You have a lamp, but the cord only reaches far enough for you to position it above Urn B. By doing so you learn that many of the balls in Urn B are red, and some are not. The light doesn’t illuminate all of Urn A, but one side of it is dimly lit. This allows you to make out the outlines of a few red balls, but not many.

You’d be wrong to conclude that the proportion of red balls in Urn B is higher than that of Urn A. You’re missing information, because some of the balls in Urn A can’t be evaluated as red or not. The light doesn’t reach them. The balls in Urn B are being subjected to special consideration; by the experimental procedure, they are put in a context that draws attention to a feature (redness) some of them have, or endows them with that feature in the first place.4 But “the proportion of red balls in Urn B is higher” is basically the conclusion I claim people are drawing with regard to the two aforementioned contexts, and category conflations in general.

The problem isn’t about sample size. It’s not that we’re testing all the balls in Urn B but only some of the balls in Urn A, and therefore the Urn A proportion has a higher error rate. The problem is that we think we’re investigating both groups when we really aren’t. You, the experimenter, can at all times see all the balls in both urns, so you expect that your inquiry captures all of both populations. But your examination of the balls in Urn B is more exhaustive, and involves mechanisms the testing of those in Urn A doesn’t. You look at balls from both urns, but you pointedly investigates redness only within one of them. The balls in Urn B have light directly shined upon them, which forces an evaluation point: they are either red or not. For most balls in Urn A, this doesn’t ever happen. If you take the non-illuminated balls in Urn A as representing the proportion of Urn A that is non-red, you are categorizing them incorrectly. It doesn’t make sense to evaluate those balls as red or non-red at all.

Shibboleths of marginalization

In one of my other posts on here—Normal Person Plus—I wrote the following:

There was never a time when it made sense to conceive of myself as a nonaddict. When I wasn’t an addict, I was just somebody who had not yet been evaluated by the addict/nonaddict shibboleth…My first real introduction to the concept of addiction—the apparatus by which society partitions people into normalized and pathologized subgroups—occurred when it became obvious that I fell into the pathologized category.

I’m not inclined to say I was always an addict or one by destiny. But it would be wrong, I think, to say that I was a nonaddict up until time t and an addict thereafter. I define addiction in terms of oppression: addicts are the group of people targeted by particular mechanisms that penalize socially atypical behaviors involving alcohol, drugs, gambling, and so on. Determining whether I was ever a nonaddict seems to require the investigation of strange counterfactuals like whether I would’ve failed random breathalyzer tests in childhood if given access to alcohol. This does happen; some children get entrapped for drug use, and I’d say those children could sensibly be construed as alcoholics on my reductive definition (whereas those subjected to the tests who don’t get trapped would be nonaddicts). But I wasn’t exposed to those sorts of situations, mostly because I didn’t grow up poor. I was in limbo, like one of the non-illuminated balls from Urn A. I don’t think that reflects poorly on the definition; I think the question is the problem, and the definition accurately identifies it as incoherent.

Addicts are the people targeted by the bear-traps of addict oppression. Nonaddicts are the people who generally step around them. But the taxonomy isn’t exhaustive. People who never encounter the traps in the first place just don’t fall into either category, at least not yet. The problem is that under most methods of investigation, this secret third group gets run together with nonaddicts. But they aren’t nonaddicts—they’re Not Applicable. Nonaddict means you’re not targeted by the oppressive mechanisms. N/A means the mechanisms (sorry to anthropomorphize) don’t know about you yet. Some balls in Urn A are revealed to be dark in color when under the light, but others just appear dark because the light doesn’t reach them. It doesn’t make sense to speculate about what color they are.

Another example: There are and were plenty of people whom it does not make sense to describe as gay or bisexual or asexual or straight. Babies! People in the year 1400! Rip van Winkle, if he fell asleep before the foundational texts in queer theory were published and just now woke up! This is why the social contagion narrative is fundamentally misguided.

It’s true that there are more queer people now than there used to be. It’s wrong that there are fewer straight cis people than there used to be. There are more of both! As time progresses, there will be fewer and fewer people who just have not had the opportunity to evaluate themselves with respect to the hermeneutical developments that have occurred, or to be evaluated—and marginalized—by other people and structures in light of them.

For any identity the having of which incurs a specific kind of oppression, the demarcation will produce three groups, not just two. There will be those oppressed by or in response to the evaluating mechanism, those evaluated and not oppressed, and then those people on whom the illuminating light is never shined. Some people just never come close enough to the bear trap that it can be determined whether they would step into or around it. Lots of people go through life without ever being subjected to some mechanism by which a given social context determines whether you are marked out for subjugation. This is true even of some people in that social context. It’s incorrect to say they’re not marked out; they’re unquantified variables. There is no such thing as the law of the excluded middle in this situation.

I think marginalization works largely by shibboleths, distinctive markers by which it is checked whether an individual falls into a group of interest or not. Bear traps are shibboleths: to fail a random drug test both causes you to be conceptualized by power structures as an addict and, in so doing, sets in motion the machinery by which you might begin to think that way about yourself. (A common result of getting a DUI or possession conviction is court-ordered attendance at twelve-step meetings. If you haven’t wondered whether you’re an addict before that, you definitely will when you hear people introducing themselves as such.)

Getting Terry stopped, or being involuntarily institutionalized, are shibboleths of marginalization. But shibboleths need not be bad or harmful in general. Some have been instantiated by identity efforts toward positive interventions. Being asked your pronouns can do the trick, if it gets you to begin conceptualizing your relationship to gender. Those operations that facilitate a person’s transition from “hasn’t yet been sorted” to “falls into the marginalized group” are what I call shibboleths in this sense. And people are not necessarily uniquely and immutably defined as members of a category or its relative complement in response to just one shibboleth. But they help make it the case that people come to conceive of themselves as members of categories, and that others regard them as such—allies and enemies alike.

Clinical shibboleths

There are also shibboleths only tangentially related to oppressive structures, but nevertheless conducive to the kind of category partition I am concerned with. For instance, clinical shibboleths: cases in which a research inquiry facilitates a person’s being understood as belonging to a marginalized category. Being given a questionnaire about your history of manic episodes is a shibboleth for Madness. So is taking a character inventory, if you’re an addict, or being asked about your eye contact and social skills if you’re trans.

Addiction and personality disorders: It is not interesting or surprising that addicts are diagnosed with PDs at greater rates than nonaddicts. Ever since the Minnesota Model-era adoption by clinics of twelve-steppy “character inventories,” addicts have been subjected to clinical evaluation for various personality disorders (or earlier, the “Axis II disorders”). Even if you think the diagnostic criteria for PDs and SUDs are correct and unproblematic, this should bother you from a statistical standpoint. It takes the proportion of nonaddicts diagnosed with PDs (or some similar control group) as the general population incidence. This produces systematic error. Addicts are routinely interrogated about their personality traits, whereas people in general are subjected to this examination only when there is some independent suspicion that they qualify for diagnosis of a PD. The subset of the general population that comes in contact with the shibboleth consists, by and large, of people who have been subjected to auxiliary shibboleths of PD diagnosis. Incarcerated people, Mad people, people who behave in non-normative ways. The clinical investigative light shines into the margin of Urn A, picking out an already-oppressed subgroup. It leaves the rest unexamined.

Then the problem compounds. For both addicts and other people subjected to diagnostic inquiry for a cluster B PD, the process of being so investigated helps to make it the case that they self-conceptualize, and are conceptualized by their clinicians, as having pathological personality traits. When a clinician asks you to introspect about whether you are self-centered, you are given to understand two things. First, an expert in these sorts of things believes this to be true of you, and hence you should probably sign off. Second, somebody with power over you wants you to assent to this evaluation; in order to curry favor and improve your immediate material conditions, it is strategically beneficial to concur. Already addicts overlap overwhelmingly with people evaluated for cluster B PDs. But also, people who are so evaluated (and are also independently vulnerable and already believe themselves to have a medicalized interiority they do not understand) are disproportionately likely to be conclusively established as having PDs.

And then the category conflation self-reinforces. After the first rush of results, it becomes part of canonical addiction treatment to do character assessments, and standard to ask people already diagnosed with PDs about their substance use. Even studies purporting not to inform the evaluators of the status of the participants inadvertently reify this. Often the entire study population has been diagnosed with some PD, and clinical assessment tools for PDs and for SUDs are largely self-report instruments. It is not surprising that studies find 91% of multi-drug addicts qualify for a PD diagnosis, with a whopping average of four PDs per person, or that 78% of BPD-diagnosed people are addicts.

Being autistic and being trans5: The conflation between autistic people and trans people has been of interest to clinicians for some time. But the researchers don’t all use the same criteria to evaluate what it means to be autistic or trans. (For example, one meta-analysis finds a dramatic difference in results between studies quantifying the coincidence of gender dysphoria with diagnosed ASD and those quantifying its coincidence with autistic screening, a less rigorous condition “measuring parameters such as social shortcomings.”) Many later studies draw from databases containing patient profiles developed under these circumstances.

Autistic people are frequently placed in clinical contexts that function as shibboleths for transness. Sometimes this is made very explicit—they or their parents are given questionnaires concerning whether they “wish to be the other gender”—but sometimes it is subtler. For instance, autistic people’s attention is often focused via various diagnostic tools, formal and informal, on their and others’ bodies: their understandings of people’s physicalities and the ways in which they would like their bodies to appear to others. Some excerpts from online autism quizzes:

This isn’t bad; it often facilitates autistic people’s ability to self-determine their physicality! But it’s weird to ignore that it happens. Clinical questions and self-diagnostic tools make autistic people aware of their bodies and the extent to which they are satisfied or dissatisfied with them, through pointed questions seldom asked to neurotypical people. “Why are you doing that with your hands?” “I notice you’re tense.” “Does the fabric of your shirt bother you?” Of course autistic people are more likely to self-conceptualize, and be conceptualized by others, as trans or cis—something many non-autistic people don’t ever do. Not everybody is trans or cis! Some people aren’t acquainted with the hermeneutics on which there is such a distinction, or just haven’t thought about it. Likewise, some people have not been evaluated by the metric of modern conceptions of neuroatypicality. But among those who have, they will disproportionately fall into an already-marginalized group. And as research into correlations self-reinforces, the notion that autistic people and trans people significantly overlap will itself motivate autistic people to meditate on their gender identity, and trans people to consider whether they are neurodivergent. Sure, a disproportionate number of autistic people are trans. I imagine also that a disproportionate number of autistic people are cis, and the fraction of autistic people who have not been marked out as either is dramatically smaller than that of neurotypical people. Marginalized people are motivated to think about other respects in which they might be marginalized. This strikes me as tautologically true.

It is good to fear

This is disturbing. I mean, the degree to which people care about and sensationalize category conflations, and use them to buttress narratives about marginalized interiority, is disturbing. The overlaps themselves are fine. As autistic activists have put it: “So what?” Nobody seems to care that a lot of gay people are left-handed or Canadians aren’t getting much taller. For it to be interesting that autistic people are trans, or that addicts are Mad, requires thinking one of those things is bad. Or at least that the correlation is surprising. But the correlation is profoundly unsurprising. Categories will conflate! No spooky theories about why must come into play.

I think it is important to be wary of robust explanations of why category conflations occur. People who are pathologized in one way will be disproportionately pathologized in other ways as well, as structures of inquiry plumb to further investigate them. There is a tendency to try to explain one pathology by appeal to others, to try to eliminate the apparent oddity of it by kicking the can down the road. Narcissism explains addiction, or vice versa: “Most addicts become involved in a chronic behavioral pattern [including] lying, criminal acts, manipulation, lack of responsibility, egocentricity, feelings of superiority, exaggeration in the expression of emotions, lack of real emotionality, and rapid shifts of emotional states” (DeJong et al., 91). Being autistic explains being trans: “autistic people can better explore and understand gender.” (Or vice versa: “gender-diverse individuals may be more likely to report higher rates of autistic traits due to…feelings of ‘not fitting in socially.’”)

I sympathize with the desire to attribute a positive meaning to category conflations, in reaction to widespread negative interpretations. But it cedes ground to naturalistic theories of identity in ways that—this cannot be emphasized enough—backfire horribly. Autonomy empowerment language, and now harms reduction rhetoric, is used to justify disabled genocide. The wrong-body model demands that trans people ritually abnegate their physicalities. Theorists have tried essentializing identitarian theories to satisfy the moderate palate before, and it always just makes things worse.

Category conflations will happen as long as baggage categories are researched. No weighty essential qualities need to be introduced to explain why. The marginalization explains it. To be subjected to the scientific eye makes people subjects, lines of inquiry into speculative hypotheses. Where you look, there you shall find.

Another paradigm case is racialization and low IQ, which I won’t talk about here in the interest of space. Maybe later I’ll type out my whole manifesto on how intelligence isn’t real.

Missouri attorney general Andrew Bailey argues that “gender transition interventions are experimental” and must be “sharply curtailed” in order to “protect children.” The ACLU sued in response; Judge Ellen Ribaudo granted a temporary restraining order against the enforcement of the rule as the lawsuit awaits adjudication.

I hate this, obviously, but not because I think people diagnosed with cluster B PDs are bad. These representations are terrible for them too—grotesque perversions, sane nonaddicts’ imagination of what we are like.

The analogy is maybe too essentialist. The light doesn’t make the balls red; it just reveals their redness. But I think that’s okay. We can just say the light subjects the balls to a contextually imposed red/non-red distinction that would otherwise be unmotivated. You don’t have to think red is a social construct to understand my point.

Autistic people are also disproportionately diagnosed with personality disorders, for what it’s worth.