"The Government Owes Me $800 but I Can't Make Myself Stay On Hold Long Enough to Get It Back": On Being ADHD

A characterization of the oppression-by-attrition model.

Philosophy, insofar as it privileges rationality and rational thought, demands that our processes of thought conform to a kind of linear structure, a structure which ADHD resists…while we typically think of ADHD as difficulty focusing, which is a large part of it, ADHD is also often experienced as difficulty organizing our thoughts into linear trains, a difficulty embodied in the writing that we produce.

Johnathan Flowers, Dialogues on Disability (2020)

How I Write

This is going to be long. My writing’s always long. I start writing and I don’t stop, and by the time I’m ready to turn something over to the relevant people, it far exceeds the length standards appropriate for the context. People respond to this with a mixture of annoyance and endearment: “Haha, Virgil’s at it again!” It’s treated as an isolated idiosyncrasy. I imagine people feel I’m pontificating—reveling in my own writing. Until I read Johnathan Flowers’s interview quoted above, I thought that too.

I will make a fundamental claim—I write this way because I’m ADHD—as a metonym for how neurodivergence operates in the neurotypical world. Then, drawing from this, I’ll critique a general structure of oppression that I call “oppression-by-attrition,” one of the paradigm cases of which is the ways in which so-called “normal function” is exhausting for ADHD people. On that note, I want to tell you a little bit about my writing methodology. At the time of my typing this, I’m just starting this piece. I have a constellation of fragmented mini-paragraphs laid out below: a sequence of disconnected and disjointed notes, incoherent except to me. Here’s a representative screenshot from the developmental stages of another piece:

I don’t write “outlines.” (Or, rather, to the extent to which I write outlines, this is what they look like.) My writings go through a first phrase in which they look like longer versions of the above. Then I go through and extend those things (in an ad hoc order) into mini-paragraphs. Then I extend them still further, into polished sections. The little fragments are like tree-branches. I pick one fragment, read it over, get into the right headspace, and expand it to match my standards of sentence structure and rhetoric. I add analogies and clarify meaning. Often I’ll get an altogether new idea while expanding one of the previous branches. In that case I’ll shift gears, make a new branch, and describe the idea. I feel a dramatic time-sensitivity while I do this. I need to beat the Forgetting Clock: if I don’t move fast, distilling the new idea and then returning to whatever I was writing before, then either the idea or the thing I was writing before will be lost to history. Hence I characterize the new idea as concisely as I can while ensuring I’ll be able to re-grasp it again at the future time that my editing has progressed to the part of the document where the new branch is located. Then I return to the section I was working on, satisfied for the time being that the “invader” idea is witnessed and notated.

This iterates: I also get new ideas in later re-draftings. By that time, the paragraphs I established in the earlier draftings are already suitably polished, the em-dashes and fragmentary structures eliminated. In middle stages, my writing resembles a lumpy blend of mostly-completed paragraphs, misspelled fragments separated by dashes, and the odd paragraph consisting only of a URL I wanted to revisit. I can’t control when the ideas arise. I know they’re my ideas—I feel like the source of them, not like I’m “channeling” anything—but in terms of their timing I am a sort of stochastic generator. Frequently I hit Enter in the middle of a paragraph. I leave it open, cutting off halfway through a sentence. Not quite subconsciously, but not in my active mind, a cost-benefit analysis takes place here. I abandon the preceding paragraph mid-sentence only when I’m confident I’ll remember where I was going with it. I draft in fractals, branches upon branches. Sorry to be meta, but at this point it’s hard to avoid: I’ve been doing all this now as I describe it. This is what this excerpt of this piece looked like at one point.

When I say “getting an idea,” I mean it very generally. “Ideas” can be new concepts— heretofore unaddressed angles of analysis of the topic. Or they can be references I need to integrate, or turns of phrase (even single words) I particularly like. As you might notice above with “iterates” and then “metastasizes,” often the same idea gets notated multiple times. (That very concept of multiple notation was, as you can see, its own idea-branch at one point.) Some of the idea-branches ultimate collapse: ideas are cannibalized by preexistent paragraphs. I don’t correct spelling or formatting within idea-branches unless it rises to the level where I worry that the “I’ll know it when I see it” threshold for re-conceptualizing an earlier idea is not met. My motivation throughout is the desire to capture the “golden event.” My idea-notations need to be eminently recognizable to my future self.

I’ve gotten pretty good at this, but occasionally I miss the mark. Currently, in one of my drafts, there is an idea-branch that reads “Were we fundamentally less democratic before the Harrison act? Maybe – amendment 17 – but in actuality maybe that amendment caused the Harrison act.” I have no idea what I meant by this. I can infer from context that I must have been talking about addict oppression as some sort of conceived precondition for democratic society. But that doesn’t help. I feel sad about this, for I recall that I was really excited when the Harrison Act idea-branch occurred to me!

Recently, I’ve been writing straight into Google Docs, Word, and Substack drafts. I used to really like Overleaf because of the aesthetic freedom LaTeX provides, but it actively frustrates my writing sensibilities. I feel compelled to comment out the ill-formatted, malformed idea branches in order to get the rendering to look pretty. At the time, I think I’ll deal with them later. But I end up never coming back to them. When I reread my documents, I look at the rendering rather than the code—but as I hope I’ve made clear, the whole reason I write out the ideas as mere fragments is so I’ll remember them. In the Overleaf arena, Forgetting Clock wins; Virgil’s Deep Self loses. My mechanism of hitting Enter and quickly conveying the likeness of the new idea is altogether undermined by the commenting feature. In fact, in the interest of trying to describe my writing methodology here, I went and looked at the Overleaf file for my M.S. thesis. The word count of the commented-out sections is twice the word count of the polished final draft. A veritable idea graveyard!

Perhaps the way I’m describing my writing here is too relatable—perhaps I’m overcorrecting for the standpoint problem. Everyone’s writing, probably, involves fragments. What I mean to get across is that mine is built from the fragments; the fragments spawn new fragments, like taking a chainsaw to a wall and then using the bricks carved away to construct new walls, and then taking the chainsaw to those. I write like this because of the way I think: because I’m ADHD. (I feel compelled to say “severely” ADHD or something, but I don’t like the word “severely” in this context.) I’d originally written that thought as “This is the way I combat the wage of what my mind is,” but the sentiment there is too negative. I don’t think my Idea Whac-A-Mole interiority is bad; it just makes certain kinds of neurotypically-coded activities like essay-writing difficult. I actually get a kick out of it. It’s energizing for me to write! The time-sensitivity is invigorating. In particular, I never find myself staring at a blank page wondering where to start. Categorically, I write too much. Seldom do I not have enough ideas to get a project off the ground.

Elsewhere on this blog I describe the Normal Person Plus model of pathology, on which abled attitudes relegate disability to particularly notable settings and erode other situations in which it is relevant. The relationship between my writing style and my neurodivergence demonstrates this. To use the somewhat crude cultural canards of ADHD, I get distracted by other trails and go off the main trail. (I don’t think that’s a very explanatory way of putting it, but eh.) But those features don’t come across in the final product of my writing, when I’ve gone out of my way to make my papers unified. In the process of revision, I inevitably refine my writing to appeal to neurotypical habits and sensibilities. It gets refracted, screened, for the purpose of making myself clear. I have to do that: otherwise, my writing wouldn’t be understood! But that erases the atypicalities of my writing; the process itself isn’t communicated. My writing appears neurotypical but long—a weirdness contextually separated from my ADHD—rather than long in virtue of my neurodivergence. My endeavor here, with this somewhat belabored depiction of my writing process, is to express through a polished writing product the feature of my writing that is naturally deleted from such products, and to demonstrate the following: (1) ADHD is more complicated, interesting, and valuable than the received view would have you believe; and (2) there is a natural and useful way to create an ameliorative definition of ADHD.

Everyone Owes Me Money

In the previous section I discussed my writing, which is an ADHD-related feature of myself that I prize highly. This second feature I’ll describe is, contextually, a negative: I often don’t receive money I’m supposed to receive. I will introduce it here and then come back to it as an example of the oppression-by-attrition model I’ll characterize later.

I don’t like money, as a concept. I’m not, like, an ADHD libertarian wringing my hands at the fact that my neurodivergence makes me bad at capitalism. If I were a money maximizer, I would go be a quant rather than a Ph.D. student who co-runs a non-monetized blog. So when I say everyone owes me money, I don’t mean it as a negative statement about my material conditions. Nor do I mean to cast aspersions: “Wow, look at these terrible people who won’t pay me back!” That isn’t the situation. And anyways, it’s not my friends, or even people I know, who owe me money. In fact, generally it isn’t people at all that owe me money. It’s institutions.

Dozens of institutions owe me money. What I mean is this: There is money out there, in the ether, that under certain moral, political, or social understandings is (or at one point was) Virgil-earmarked, but which I never did and never will receive. The reason why is—on standard interpretations of how social interactions work—my fault. I’ve written for journals and blogs where I was told there would be an honorarium, given detailed instructions about how to solicit the honorarium, and then never did. I’ve participated in clinical trials, received payment cards, and then lost them. Time and again, I’ve failed to submit invoices for contract work or receipts for reimbursement.

This happens to everyone occasionally. For me, it is not occasional, not even statistically significant, but overwhelming—it is the standard thing that happens when I work in a context where the norm is a bespoke payment plan rather than direct deposit. I should know better by now. Fairly often, I do things (writing, clinical trials, contract work) because there is a monetary incentive. But I almost never get the money, despite the fact that receiving the money is precisely my reason for doing the thing in the first place. In fact there have been many times when I really needed money, did some work to get money, and then failed to put in place the administrative steps on my end required to receive it.

As with my writing style, my relationship to money—and in particular this phenomenon of not getting money I’m supposed to—is about my being ADHD. So again I want to tell you a bit about what goes on in my head when this happens. I know I’m supposed to write up the invoice, or collect my receipts, or whatever, and I know there’s a deadline. But I cannot get myself to consider the task pressing or urgent. That isn’t because it’s not pressing or urgent; my experience of ADHD isn’t “I procrastinate because I can only do things when there’s a hard deadline soon.” Rather, the problem is that this particular kind of logistical task (one involving some administrative busywork and requiring commitment across time or routinely checking in on something) is categorically the wrong sort of activity for my mind to designate urgent. That designation is orthogonal to the importance and time-sensitivity of the task. Making appointments, getting medication refills, sending overdue logistical emails, and checking on the status of my tax refund all get sorted into the same “unimportant” box.

I tell you this because I want to emphasize that the reason institutions owe me money I’ll never receive isn’t about distraction. It’s not “Foiled again!” I’m not Tom, trying to defeat Jerry but never quite managing it. My writing process is halting and self-similar because my mind, when I write, is a sporadic conductor rather than a continuous one: I get “interrupted” by generative ideas, not by birds and squirrels. (I hate the squirrel analogy!) Institutions owe me money because dotting “i”s and crossing “t”s is not something I can get myself to do—not because administrative tasks are, like anything else, something I can easily be distracted from.

(Editorial note: Originally I had a long middle section here about an idea-branch called the “autistic-or-nothing double bind of neurodivergence,” on which ADHD testimony gets reinterpreted to make it sound either like autistic self-reports or like neurotypical ones. I deleted it because it was too long and basically unrelated from the rest of the content here. I’ll make it a separate post if there’s interest.)

The Oppression-By-Attrition Model

On the received Normal Person Plus view, ADHD constitutes a volitional deficiency: you’re a ball of dust buffeted by the wind, vulnerable to intrusion by noises or the sight of a squirrel. It should now be obvious why the distraction metaphysics of ADHD is impoverished. If I were categorically too distractible to complete involved tasks, I wouldn’t have written this post. Or done the contract work that I’ve done but not received payment for. Or done anything ever! The whole distraction thing is unserious.1 More generally, the phenomenology of ADHD is more robust and interesting than being “easily distracted” (which isn’t to say that it’s essential or context-independent). It travels with valuable interior experiences, many of which crucially affect the day-to-day lives of ADHD people but get cloaked under the NPP view of ADHD as an attention disorder.

A question I ask a lot on this blog is, “What is it like to be X?” (where X = some identity). In the above I tried to present some insight into what my experience of ADHD is like. Of course, ADHD is to some extent multiply realizable—I doubt my testimony will generalize to every ADHD person. Besides, I think that discussing the generating mechanism of ADHD or distilling its “biological features” is misguided and counterproductive (I’ve made the same point about addiction). The most useful and explanatory notion of ADHD is the one that defines it as subjection to certain forms of oppression. I call them oppression-by-attrition; although the attrition model in full generality is expansive and also marginalizes non-ADHD people, it’s suitable for my purposes here. The account I give of my experience of ADHD will hopefully provide some insight into how oppression-by-attrition works. (I’m not sure whether I mean for this post to function more as a definition of oppression-by-attrition—in which case my ADHD is a case study—or as a definition of ADHD, in which case my description of oppression-by-attrition is. Death of the author or whatever.)

Oppression-by-attrition is a common structure among certain kinds of institutional, political, and conceptual mechanisms that facilitate the subjugation of disabled, Mad, and neurodivergent people. These oppressions aren’t the same ones I claim hold for addicts (although obviously ADHD addicts, like myself, will be affected by both). In a previous post, I described addict oppression as involving a bear-trap model (embedded here):

In summary, bear-trap oppression occurs when you are coerced into behaving in atypical ways, which serve the functional role of justifying the harms you sustain on the grounds of your or others’ best interests. The canonical cases are racialized stop-and-frisk policy and random drug tests. Crucially, bear-trap oppression is self-reinforcing. It not only instantiates but also legitimizes the subjugation its victims experience.

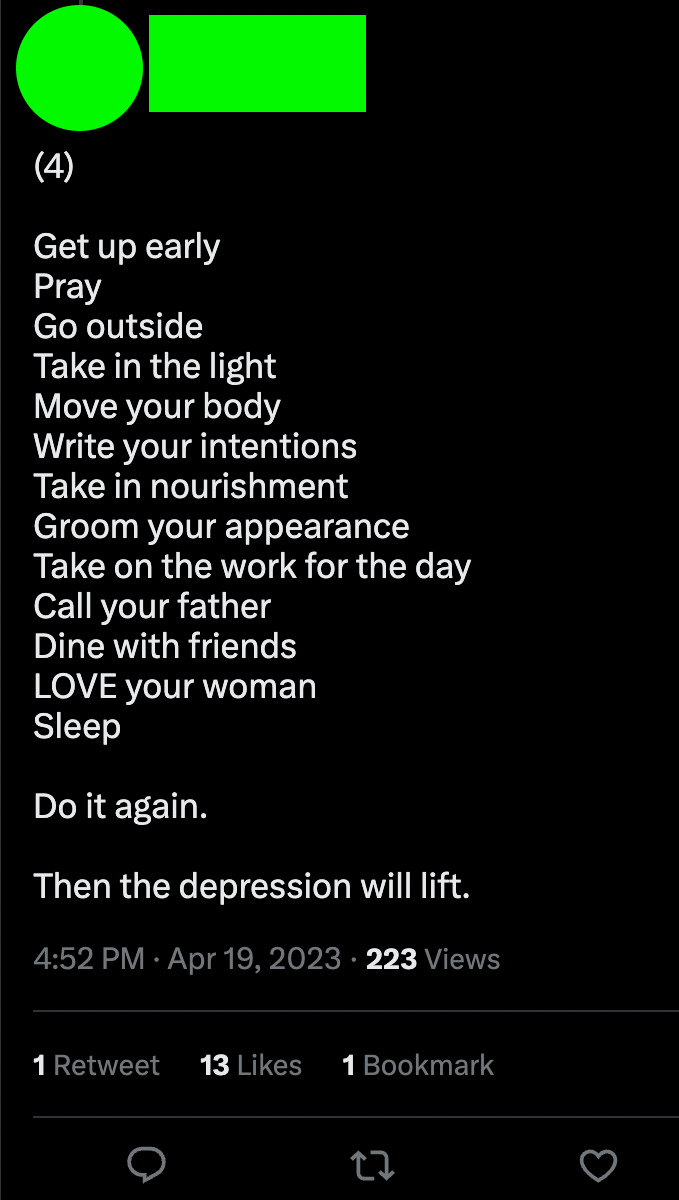

I characterize ADHD oppression as instead operating through a different model. While bear-trap oppression produces the illusion that the harms you experience are deserved or required, oppression-by-attrition produces the illusion that the harms are easily soluble through simple fixes that you yourself could enact. You don’t need intervention, assistance, or positive access—you just need to make the appointment, submit the receipt, take your meds, go outside.

The sociopolitical world is an unending sequence of wars of attrition levied by institutions against people: situations in which a person pursuing some goal faces insidious institutional backlash that needs to be handled expertly in order to accomplish the goal. Think about negotiating with insurance companies about their paying your medical bill. Think about tax returns, the rigamarole of mailing packages through the post office, being put on hold for hours by a company while attempting to settle some dispute. The key qualities that allow a person to win a war of attrition are patience, commitment, strong desire to accomplish the goal, and—crucially—the ability to conceptualize the goal’s accomplishment as urgent. To put it simply (although I don’t love this phrase), you need “executive function.”

I use the term “institution” generally here. If we take “institution” to mean “bureaucratic governing structure,” then there need not be institutions of any type involved. Oppression-by-attrition is not always reducible to oppression by bureaucratic silliness/negligence/malice, although bureaucratic silliness, negligence, and malice often facilitate oppression-by-attrition. “Institutions” can be social practices like promise-keeping or relational structures like civil unions. Hence oppression-by-attrition may resemble being marginalized by the pace or setup of society (a la Susan Wendell) in contexts separable from, but ultimately related to, bureaucratic operation. Or it may involve agreements between individuals (i.e. having a hard time meeting deadlines you yourself set), or specific received views about social responsibilities. I give examples herein involving literal bureaucratic institutions merely because I think that provides a cleaner insight into what goes on when oppression-by-attrition happens.

As for “backlash”: I just mean an individual’s attempt to change their circumstance meets friction. When the oppression is instantiated by an institution, the “backlash” need not be personalized, vindictive, or even broadly intentional. To be fair, in many cases the backlash is systematic and deliberate. (Of course insurance companies make it difficult to get them to pay for stuff. It’s obvious why they do that!) But not always. Up until recently, the federal government owed me around $800—the amount I overpaid in 2021 taxes. I don’t think this constituted a scheme to take away my money. I confusedly consulted with the people around me, all of whom seemed to have gotten direct deposits fairly rapidly after doing their taxes. I waited as May and June 2021 passed. August rolled around, and I still hadn’t received my refund. The IRS site indicated that the government had received a record number of tax returns this year, and the processing was slow-going. Under the “If you haven’t received your refund yet, here’s what to do” blurb, I saw the thing I dread most in the world: the customer service information.

I made some endeavors to call the IRS (woke up thinking “I’ll do it today” for a few days). I did, in fact, get around to calling, but in order to assist me the automatized system needed information that would have required me to dig through files—to perform more administrative tasks. I resigned myself to never getting my $800 back.

Most of the other people I knew had submitted their tax return forms online. I hadn’t. I’d mailed the forms because of another war of attrition I lost. In order to submit electronically, I had needed to find information that I couldn’t work up the motivation to search for. The IRS website said that they were currently going through mailed returns—that was the source of the lag; the electronic returns had all been processed. So I found myself in this second war of attrition because of a previous one. Oppression-by-attrition iterates. This comparison case is a useful one:

Like poverty, attrition compounds. Start by not having the wherewithal to contest a medical bill; end up in a war of attrition about medical debt. (Indeed, this is the premise on which the companies that buy medical debt work. Like insurance companies, they target the impulse to just give up—preying upon people in general, but in particular upon the people marginalized in light of non-normative conceptualizations of salience and urgency.)

Weirdly, I actually did get the $800 back. Late in 2022, the monies were deposited into my account without my having to do anything about it. I know that kind of defeats the contextual purpose of the narrative. But the reason I remember this whole situation so vividly was because it is wildly anomalous for me to actually get the money in these situations. Practically nothing else like this random $800 deposit has ever happened to me. I could tell you dozens of stories of negotiating with insurance companies in which I was absolutely in the right but quickly gave up, on threat of medical debt, and just paid a several-hundred-dollar bill that I couldn’t work up the urgency to advocate for myself about, even though I totally could not afford it.

The above elaborates upon one key axis of oppression-by-attrition: the attrition part. The other important attribute of the oppression is the general perception that it is in fact easy to win the wars of attrition. Oppression-by-attrition makes it so that you are widely regarded as capable of completing, but do not successfully complete, ostensibly simple “hacks” with the aid of which you would escape harm. This constitutes the way in which oppression-by-attrition, like bear-trap oppression, is self-reinforcing. It justifies your suffering. While bear-trap oppression promotes the interpretation that the victims’ suffering is justified on the grounds of their desert or dangerousness, oppression-by-attrition instead utilizes the narrative that your suffering is justified on the grounds of its escapability. No one claims that you deserve to suffer. Rather, your suffering is perceived by others as having an easy off-switch—and hence not worth getting concerned about—when in fact the off-switch is inaccessible to you. If you really didn’t like the situation you’re in, you would just noclip out (like all these abled people have done in similar situations to yours). Bear-trap oppression is facilitated by the idea that the victims are somehow different from the non-trapped people; oppression-by-attrition is facilitated by the idea that they aren’t.

Recall: Bear-trap oppression isn’t unique to addicts. (The paradigm case of bear-trap oppression is Terry stops, geared towards Black men. Moreover, I think Bettcher’s deceiver-pretender double bind operates as a bear-trap for trans people.) Nor is oppression-by-attrition unique to ADHD. There are many communities marginalized by it. Another neurodivergent group that I think is obviously subjected to oppression-by-attrition is autistic people. Though its scope is probably even wider than this, I think oppression-by-attrition is peculiarly relevant to neurodivergence, Madness, and invisible disability. For example, we’ve all seen those silly tweets about how depressed people just need to go outside:

Leave aside the question of whether the alleged off-switches actually work; that is totally irrelevant to the operation of oppression-by-attrition. The point is that if they exist, they are inaccessible to you, but the illusion produced is that they are existent and easy for you to access. Hence, to the people around you, it appears that the mechanism for getting yourself into a better situation is very much within your grasp! To fail to make use of the mechanism means you don’t want to improve your circumstances enough.

Like I said above, I don’t mean for oppression-by-attrition to be coextensive with bureaucratic absurdity. But I do think that the absurdities of bureaucratic function are usefully metonymic in the context of oppression-by-attrition, in much the same way that carceralist sensibilities are broadly relevant to the consideration of bear-trap oppression. Carceralist attitudes crystallize the undergirding reason why bear-trap oppression is carried out uncritically: “There are dangerous people, and we need to catch and incapacitate them.” Likewise, the sensibility of bureaucracy facilitates oppression-by-attrition, even when no actual institutions are involved. It tells us that systemic function ought be individualized. Each person has a cog-like part to play. People are ultimately accountable for their carrying out the requirements delegated to them. Other individuals’ responsibility to them is limited. Kick something over the fence and your work is done; you’ve passed off the task. When we teleologically self-interpret as sorting mechanisms within this sort of intricate hive structure, we extrapolate our interiorities to those of the other participants in the structure—even though we only ever see a small quantity of the vast cogwork around us. Ostensibly simple tasks, performable under a straightforward one-size-fits-all mandate, are the bread and butter of the bureaucratic-delegation model of social function.

Given the nature of oppression-by-attrition, it’s ironic what the “H” in ADHD stands for. My experience of ADHD is not of bouncing off the walls, but overwhelmingly of exhaustion—getting too tired to continue performing some intricate administrative task. I feel that same sense of doneness now. Writing this is no longer salient; I feel like I’ve made my point and wrapping things up is a logistical thing that my mind can’t qualify as important. So, hoping that I’ve characterized my ADHD sufficiently that my reader will forgive me for this, I won’t bother to.

Of course neurotypicals have proposed responses to that diagonalization; their responses follow the aforementioned-but-not-elaborated autistic-or-nothing double bind of neurodivergence. E.g. “ADHD people can summon the willpower to do the stuff they want to do,” in which case we’re just neurotypicals, unless the stuff we want to do constitutes special interests, in which case we’re autistic.