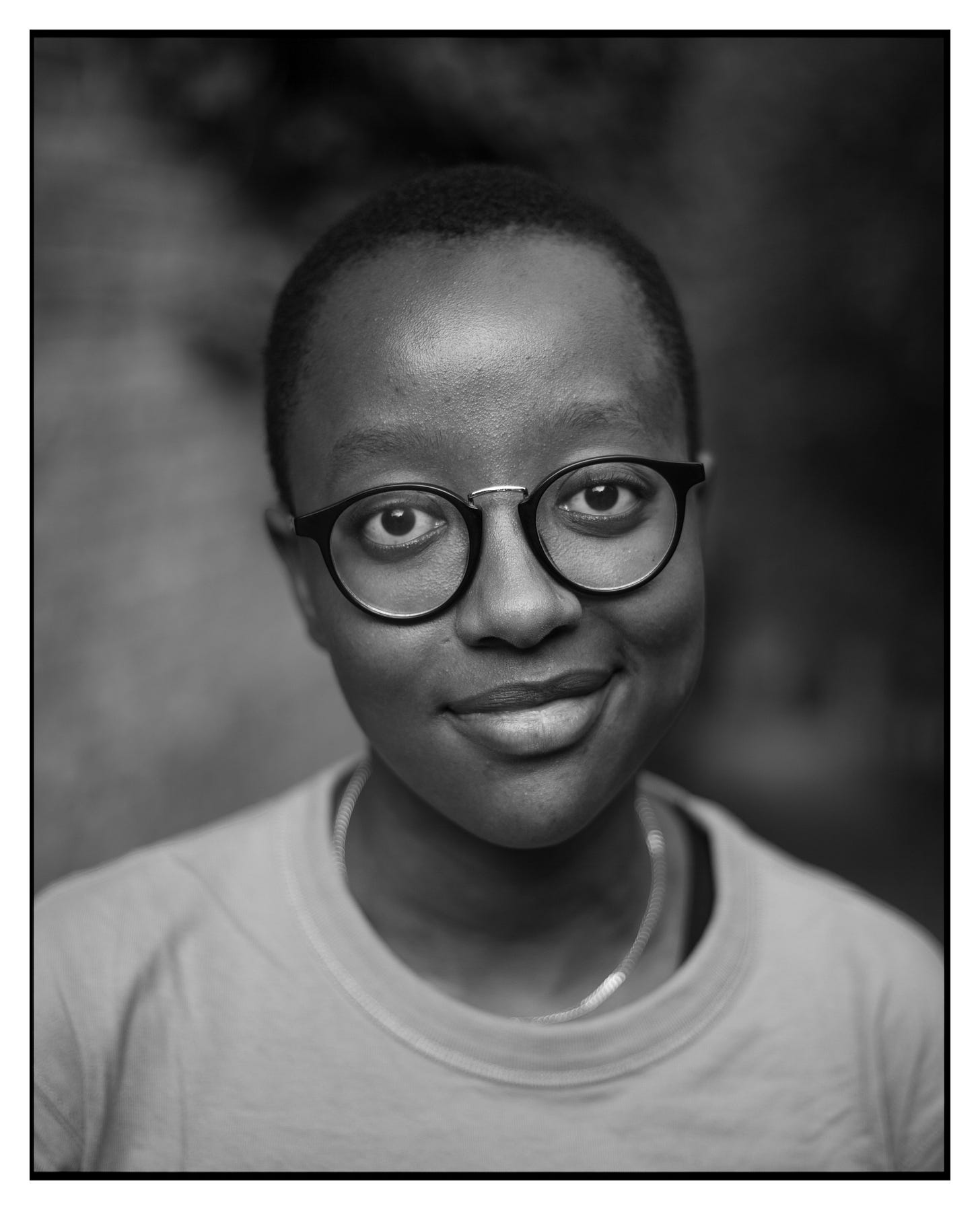

Discourse with Waithera Sebatindira: "Sobriety taught me about mutual aid"

T. Virgil Murthy and Waithera A. Sebatindira talk about recovery communities as revolutionary centers of care.

This week I held the third entry in this series with Waithera Sebatindira, author of the newly published book Through an Addict’s Looking Glass.

The publication page at Hajar Press describes Waithera as “a Kenyan writer based in London. Their previous writing and research interests have included food imperialism, drag kings and gender transformation.” They are also a co-author of A FLY Girl’s Guide to University, a set of reflections by women of color on their experiences at Cambridge University. American essayist Sonya Huber calls Through an Addict’s Looking Glass a “meditation in spiral crip time” that “weaves disability and black feminism with spirit, justice, memory, recovery and community.” (I concur—this book is great, and my commentary on it will be out soon!)

In my interview with Waithera, we discussed crip time, intergenerational addict epistemology, religion as revolutionary, decarceralism, and the radical prospects of recovery communities. The interview transcript is here.

Addiction and crip time

TVM: Waithera, welcome to Discourse! Thanks so much for joining me.

I’d like to start by talking about the dedication to your book: to a person, you write, “for whom I’d have built a new world with my bare hands if I could” (5). I had a very visceral response to this quotation. What does it mean to you to build a new world—for ourselves, for the people we have or have lost, for addicts in general?

WAS: There’s something about inevitability there. For me, a big part of building a new world is grappling with, for instance, Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s definition of racism and oppression. There are categories of us for whom certain outcomes are more inevitable than for other people. The first element of building a new world is eliminating that inevitability. It’s not so much that I think the misery and death of marginalized people is itself inevitable under current conditions—one of the things I talk about in the introduction is the idea of addict livingness (drawn from Katherine McKittrick’s phrase ‘black livingness.’) Addict livingness means that in the face of circumstances that kill and immiserate addicts, there is still crip joy.

Then there’s a creative function as well. Building a new world is an abolitionist task; it requires us to take down those things that make certain outcomes inevitable. But it also involves creating new possibilities. I wonder a lot about what the futures of people we’ve lost might have looked like: if they had had the access they needed, if the ways in which the world sickens us were eliminated, if human dignity were placed at the forefront of things. Whatever institutions and norms we could create around that are a crucial component of the project.

TVM: I really like your focus on eradicating this inevitability. The immutability of addict suffering, the fact that we cannot think our way out of the reality in which people are in imminent danger, is a central aspect of my own experience of addict community. It dictates how I view the urgency of this situation.

WAS: Exactly. People experience this urgency in many ways. Being middle-class has shielded me from some of the wage of addiction, but not from this gravity. Addicts know the feeling of urgency so well, of needing things to change. The care that we give to members of our community operates on a minute-by-minute basis. That’s what’s at stake; those are the timeframes we’re living within in active addiction.

TVM: You invoke multiple experiences of time: most centrally “it’s-not-time” in active use and “sober time” in remission. I thought your distillation of the time concepts was a good way to escape the typical canards of addiction. “It’s-not-time,”1 I think, places the urgency of addiction back on our own terms. Similarly, you point out how “sober time” importantly diverges from “straight time” in its sense of motion through failure and progress, which beautifully illustrates how maintaining sobriety isn’t some sort of seamless reentering of the abled world.

WAS: Right. The book is definitely not an attempt to explain addiction to nonaddicts, and I don’t want nonaddicts to read it and say, “So this is what addiction is like.” But I think by focusing on the phenomenology of time, we can capture both the intensely personal features of addiction and the eminently material ones. Much of what makes life livable or unlivable is class considerations, which are so relevant to the experience of addiction. The time concepts, I hope, capture both the interiority of life in active addiction and the political context of that interiority.

TVM: One more thing on the general “time” topic. You write about how time-consuming it is to experience the world as an addict, whether in use or remission. You describe your experience as “a transparent bubble submerged in the stream of ‘normal’ time” (10), and point out that “sober time simultaneously gives me the ability to participate in straight time and consistently pulls me out of it” (22). Something Anna and I have discussed a lot is the major accessibility barriers that marginalize addicts but don’t occur to nonaddicts. Like, if you’re addicted to an illegal drug, you cannot have a 9-to-5 job. You touch on that in your disability chapter, and address in Imago Dei the addict economic precariat. People don’t really get this, the way in which that sort of crip time cuts against social and economic access.

To clarify my question here, I’ll bring up another comment of yours, about the relationship between your time and your communities’ and friends’ times: “I slice diagonally across the musical phrases that make up their lives” (34). Having to excuse yourself from public settings to use, for example, really puts in nice relief the ways in which bringing together crip time with this hermeneutically dominant and uniformity of linear abled time creates a conflict. There’s this notion from the disability literature called “misfitting,” due to Garland-Thomson. It’s this stigmatizing experience that occurs when you put the disabled experiential paradigm in conversation with the abled world. The canonical example is a wheelchair user juxtaposed with a staircase. The incompatibility creates an oppression. So I wonder whether you think that the co-occurrence of these different kinds of time, the holding to one standard of people who are living in the other, manifests as an ableist oppression. You do emphasize at some points that the crossovers between different time experiences can be productive. So what, exactly, is going on there when those two kinds of time intersect?

WAS: The first thing I want to say is this. Part of the reason I’m able to provide a positive conclusion to that part of the book is that I’m lucky to have a friend group that is quite disabled. I’m the only person who would identify as an addict, but it’s a group with many disabled people. Part of my own realization in recovery was that other people are occupying crip times as well. Then on another level: normative ideas of straight time are a social construct. Even abled people are also occupying their own strange, asynchronous kinds of time. To the extent that you have an archetype that people can deviate from, perhaps the more you deviate, the more you’re able to see that others are deviating, even if only slightly.

And then on the ableism point—the injustice of that juxtaposition of times—I’ll say this. I was in university for most of the worst of my drinking. It’s almost hard to talk about it as an injustice, because drinking and drug use are such a common element of the university experience. Turning up hungover to lectures, not being able to concentrate: that’s just what students do. But there is a particular injustice of this for the addict. You can’t really participate in university, or in normal life in general, especially if you’re addicted to an illegal substance. University is a particularly good example because there is an idiosyncratic mix of regimented and free time. Because of that mix, there is a theoretical possibility of flexibility; education in general is an easier space to accommodate disability in principle. But it doesn’t realize that opportunity to accommodate disability, because it is meant to teach us to be compliant workers. So even though there is potential for accessibility, it goes unfulfilled—otherwise we would not be able to turn up for the 9-to-5s we are expected to hold when we leave.

I was particularly conscious of that. I was so self-hating at the time that I saw myself as a problem. But now I see that as a profound injustice that could so easily have been lessened, mitigated, even eradicated.

Addict epistemology

TVM: This reminds me of your discussion of your first experience of DTs, with which you open the book. To summarize for our readers: The book opens with a parallel-verso poem, one side of which recounts your thoughts the first time your hands shook, and the other of which recounts an early memory of your grandfather’s hands shaking as he cared for you in your childhood. Both sides conclude with “I know why my hands are shaking,” as you draw the connection between these two events. I read this as your reinterpreting your family’s relationship to alcoholism in real time as you saw it happening to you—is that correct?

WAS: Yes. That was a hard part of the book to write, practically speaking. I chose to leave it ambiguous partly because of wanting it to read well as a piece of art. That memory was, for me, very strange. I was hesitant to talk about my family too much in the book itself, but this is a family illness. And yet, like I say in Memory Failures, I don’t think I’ve had any other experience like that, where I just rediscover a memory that feels like it was hidden in my brain. My recollection of my grandfather’s hands was a really banal, normal moment at the time. I can’t explain why it was lodged in my brain, but it made its use known when it needed to be known, in a life-changing way.

TVM: I’ll ask you more about that opening, specifically, when we get to the next topic. But for now I want to relate it to addict epistemology more generally.

I’m the first in my family. When it became obvious that I “could not drink responsibly”—that I had this relationship to alcohol that others did not have—I was extremely confused. A lot of the other students around me figured it out pretty quickly, but it wasn’t a hermeneutics I had access to. As you mention, if you’re in college, it really feels like everyone’s drinking as much as you are, at least for awhile. (In retrospect I realize that from childhood I saw alcohol very differently from other people, but I didn’t understand that then.) Eventually I had traversed enough of the runway that it became clear other people weren’t blacking out every time they drank, and I was. But until then, I didn’t realize this was unusual, because of the general canard that everyone drinks so much in college.

WAS: Even though I was aware of the alcoholism in my family, I never thought that had anything to do with me. It wasn’t until my hands shook that I made the connection. Yet I knew from the beginning that there was something strange about my drinking—something unconscious or semi-conscious. As a teenager I self-described as having an “addictive personality.” Before I started to drink, I had a sense that I probably would have an issue. I was scared of alcohol before I drank it, and was a weird drinker from the very beginning. And yet carried on. But equally, there are other things that I was aware I should stay away from, and managed to. I’ve never smoked or gambled—I had an instinctive sense about it. I knew I would have a strange relationship to them. But with alcohol, I had that same knowledge and still went down that path. It wasn’t a choice, and isn’t something I’ve thought too deeply about, but is something I’ve always been intrigued by.

TVM: In full generality, I’m critical of the concept of the “addictive personality” the way it gets used in folk psychology, but I do think we need a hermeneutics for people who are vulnerable to this sort of thing, structures that prey on habits. The way you talk about it makes sense to me. For me, alcohol was always different. I was afraid I’d “get addicted” to various medications, but I never have. So my question is: Are you saying that you reflectively realize your relationship to alcohol differed from the other things you felt you should stay away from, just based on the empirical evidence? Like, alcohol was different only in that you weren’t successful in staying away from it? Or do you feel, phenomenologically, like the desire to drink was actually stronger than you felt for other substances or processes?

WAS: I think it’s the latter. You said you had an atypical interest in alcohol from when you were young. I don’t know if I was drawn to alcohol itself, but addiction to it always made sense to me in a way that, perhaps, chain-smoking has never made sense to me. The specific memory it brings to mind is this: have you ever watched True Blood?

TVM: I’m vaguely familiar. It’s the TV show where the main character has to pick between her two vampire boyfriends, right?

WAS: Precisely. There’s a character named Tara whose mom is an alcoholic, and in one scene Tara confronts her about her alcoholism. Tara spills the vodka her mom was drinking onto the carpet. And her mom immediately gets on her hands and knees and starts trying to suck the vodka out of the fibers of the carpet. It’s a very abject depiction of alcoholism. I was watching this as a teenager who had never drank alcohol, and while the camera was on Tara’s mom, my thought was: it makes sense, if there’s no other alcohol in the house. I understood what she was doing. And then the camera pans to Tara’s face, and Tara looks horrified and confused. I then realized that I was supposed to be having Tara’s reaction, and not the reaction I was having. I thought: “I understand this is supposed to make us have contempt for this woman, but her behavior makes perfect sense and no one can convince me otherwise.”

TVM: In Normal Person Plus I talk about this a lot. I feel like I have these two superimposed perspectives that are not compatible. I’ve seen that look of bafflement on so many people’s faces. I’ve mentally modeled having that reaction so much that I almost know what it would be like. But my real reaction is, why would you not finish other people’s abandoned drinks? Makes perfect sense! This is the important feature of addict epistemology: there’s this whole way of viewing the world that has been decreed irrational by power structures, basically. But absent that externally imposed definition of the normal, I don’t see why I should think my default impulse is wrong and the other one is right.

WAS: I think that all the time with morning drinking. It’s the symbol of alcoholism; that’s when you know you’ve “gone too far.” Try as I might, I can’t elicit the response to drinking in the morning that I know everybody else around me would have. I was in a group one morning and I noticed someone was drinking from a cider can, sort of furtively. (I wouldn’t have thought to look at what he was drinking except that he was drinking in the way I would’ve been drinking. A very specific way of moving. I knew even before I looked at the can what he must be drinking, if he was drinking in that way.) My first thought, rather than “This guy has a drinking problem,” was “I guess I’m supposed to think this guy has a drinking problem.” Personally, I’ve never understood the rules about the times that drug use is permitted. For me all time is drug time. If you’re awake and conscious and can take a drug, then it’s drug time. So it was another reminder to me of that different experience. I thought that before I read Normal Person Plus, but I really loved that piece because I think you have got it spot on. “I cannot elicit that feeling that says this is fundamentally abnormal and problematic, even though I know intellectually that I’m meant to think it is.”

TVM: You say your first response was “I’m supposed to think he has a drinking problem,” rather than a reflexive “That’s a drinking problem.” That puts it beautifully: we learn inductively that we’re supposed to have this reaction. Just a constant mental modeling of nonaddicts that goes on in our heads.

Intergenerational wisdom in addict communities

TVM: Back to Guka’s Hands, the first chapter of your book. I really liked the ambiguity in that section. I noticed a sort of Easter egg, which is that one of the tracks on the playlist for the book (page 7) is Bill Withers’s song “Grandma’s Hands.” The song conveys a somewhat different picture of the pedagogy of older hands. I really liked that juxtaposition: there’s two kinds of generational wisdom being passed on. One in the sense of nurturing and care, and the other in the sense of transmitting knowledge about membership in this marginalized community. This second point comes across in your introduction: “Not only are the knowledge practices that addicts develop in active addiction and recovery useful for saving our own lives; they also add a specific and valuable lens to humanity’s kaleidoscopic understanding of itself and of the world” (11). There’s an intergenerational teaching project at play here.

WAS: I’m really glad that you made that connection with the Bill Withers song. Of all the playlist choices, that was the most intentional. The theme of care plays so strongly in the song and in that memory. When I think about my grandfather’s hands shaking, now, it means he made a choice not to drink because he wanted to care for me. To nonaddicts, of course, that seems like the bare minimum. But as an alcoholic I know how excruciating that must have been, and I find that so moving. There are no words.

Then there’s also the element of care where that memory was made available to me when I needed it. I can’t say I’ve given a lot of thought to the afterlife, metaphysics, I just accept whatever strangeness happens. But even after my grandfather had died, there’s the idea that he had a hand in bringing that memory there for me that day.

TVM: The fact that you, as a child, intentionally decided to retain that memory, and then it resurfaced when you needed it.

WAS: Yes. It feels like there must be a caring hand involved. It’s not enough just to say it was my grandfather speaking to me from beyond the grave. It’s the strangeness of my five-year-old decision to remember that moment, even if for the wrong reasons. It tells me something bigger than all of us, something that cares for me, is in the world.

TVM: It’s such an evocative vignette.

OK, onto the question, and it’s going to be a long one. I have this concept I keep trying to get other philosophers to pick up: intergenerational erasure. In disability activism we always talk about eugenics. “Eugenics is how abled people oppress us; eugenics is how attempts to erase us from the world proceed.” But to my way of thinking, eugenics isn’t just about preventing people from being disabled and disabled people from being. That’s plenty nefarious already, but eugenics is just one among many institutions that together play the much larger and more strategic role of preventing disabled people from organizing. Another such institution I enumerate is family separation. (There’s also restriction of immigration, which I don’t much discuss.) Basically the idea is that various political interventions are used to prevent marginalized people from talking to each other—creating communities and activist projects that persists across time, and developing the hermeneutics, the solidarity, the resources to enact them.

What we always see with backlash to liberation is “These people are dangerous to children.” It’s intersectional—say, the crack baby canard closely linked to Black addict oppression. Currently it’s omnipresent in anti-trans backlash, this pernicious stereotype that “trans people are coming for your kids.” The intention of this is more than just to incite violence against trans people and isolate them from everyone else. It’s meant to isolate them from each other—children from adults. It’s a large-scale, profoundly effective tack to make it such that trans activism exists for exactly one generation, and then dies. Because if you can’t communicate with children, there will be no children to take up the project. This separation between generations, “you can’t teach your politics to my kids,” puts a horizon on the organized efforts for justice by cutting off posterity. The community lives and dies in a single generation. Intergenerational persistence is the only way activist communities ever get things done—so when intergenerational erasure is instantiated, the agitation runs out of oxygen and nothing changes in the long term.

The opening of your book is one of the most beautiful examples I’ve seen to date of the intergenerational solidarity and meaning and development that the addict community can provide. You describe this particular kind of insight you’ve been given. And of course it’s mysterious, the circumstances strange and mystical. But it’s received wisdom, and care drips from it. That’s why I found the Bill Withers attribution so poignant there. If intergenerational erasure is the big nefarious thing I am afraid of, this intergenerational passage of information through memory is its opposite. Do you feel like taking on mentorship roles, aiding others within your recovery community, is an opportunity to participate in this general project of passing on knowledge?

WAS: I love that. That’s such a good way of putting it; that is, so much, what it feels like. It involves a lot of sharing information: “This is what worked for me; maybe it’ll work for you, and if not there are all these other people who can share what has worked for them as well.”

The information varies in kind. When I first came into my recovery community—I think this is funny, but maybe only because I survived—I learned about 24-hour alcohol delivery because someone else talked about it. And other active use practices too, because it took me awhile to get sober after I started coming. So there are different kinds of knowledges being shared in these spaces. The overwhelming majority of them can have the potential to save our lives. But something very human is the fact that within that, unintentionally, tips can get mixed in that are conducive to active addiction. These two kinds of knowledges exist in the same place, but the ones that saved my life have been the dominant ones.

TVM: I talked about something adjacent to this with Maia Szalavitz. There are needle exchanges around the corner from twelve-step meetings. These two kinds of knowledges not only can coexist harmoniously, but keep our whole community—active addicts and abstinent ones—alive and working together. In one piece I’ve written for the blog I made fun of Judge Glock for saying something like, “Why are harm reductionists hiring addicts? What could one addict teach another, except how to score?” I think this is just a failure of imagination. Maia’s written about how another user told her to clean needles with bleach, and so saved her life. Sure, maybe advice like “here’s how you get alcohol delivered to your house” isn’t very helpful to anyone. But a lot of the received wisdom of “here’s how you stay alive in active addiction” is incredibly important community knowledge.

Religion and revolution

I believe in a materialist God. One whose primary tool is the world as it exists, not as humans wish it existed. This means that God must work through disability not to eliminate it or to inspire the non-disabled but in the same ways that God works through everything else in creation. Sometimes to produce a radical shift, sometimes to enact a quiet change unknowable even to the changed being itself, always in accordance with God’s will and not the demands of the political economy of the day (52).

TVM: In a lot of leftist spaces, religion, and Christianity in particular, is not very well-regarded. But two great chapters of your book are devoted to the relationship between religion and liberation. So I’d like to ask: how might we distill the insights that religion and spirituality can provide to addict liberation, disability liberation, Black feminist theory? How could we get the kind of leftist who is dismissive of organized religion on board with your vision of a materialist God?

WAS: My first feeling is that people are drawn, if not to religion or spirituality, then to the desire for something bigger than themselves. I don’t want to make sweeping statements about people’s relationships to God or to the immaterial, but at least something bigger. You see that across a range of groups, including amongst Marxists—be it veneration for certain thinkers, or be it the recognition of the cathartic, beautiful feeling that comes from being part of a community that is devoted to something bigger than all of us. Those feelings are found in churches, in vocations, even in workplaces. I work at a law firm, and the way lawyers talk about their clients, their willingness to sacrifice—there’s a real sense of purpose in that.

I don’t know if this argument would convince anybody. You tell the leftist at the political rally, “People are relating to something bigger than themselves in a way similar to what religious people do.” The response is, “Well, why not have Marxism be the higher power; what does God have to do with it?” So the smaller point I make in the book is this: the reality is that significant swaths of the population do believe in a God or gods. I’m less interested in getting atheist leftists to understand why, and more interested in making them take it seriously.

TVM: I know it’s annoying to say—kind of just a gotcha at this point—but so much of the style of Marxism that claims religion is stupid and inherently oppressive is, you know, so white. I don’t just mean its proponents are literally white; I’m not claiming that being white makes people context-independently bad knowers. I mean it in a Charles Mills sense: the whole enterprise uncritically adopts this racialized neoliberal machinery. The way secular humanism has been taken up is as a reification of existing power structures. And sure, it isn’t controversial to point out that New Atheists aren’t subversive. They’re eugenicists. But a lot of milquetoast secularism is much the same.

WAS: If I’d had more time, I would have liked to address this in the book. Claims of secularism are always seen as, if not neutral, then revolutionary in and of themselves. There’s no willingness to consider that the secularism propounded by many of these leftists is very much part of the post-Enlightenment project, very much not their own invention. The very fact that they think it is the product of a free mind, ahistorical, maverick, is itself part of the post-Enlightenment project! And even among the people who wouldn’t be surprised to hear me say this, there isn’t a real sentiment that we should be grappling with that, that it’s a problem. Often the response is just, “Okay, you’re right.” People view it as apolitical. There isn’t a sense of secularism as an ideological battleground that has to be critiqued alongside all the others. What priority it should be given, I don’t know, but it will have to be fought at some point.

I guess maybe one baby-step is the taking seriously of spiritual epistemologies. To go to your point about whiteness: I don’t think one can seriously call themself an internationalist while at the same time deprecating anyone who believes in a God. One can’t call for global revolution while being dismissive of anyone who ties the revolutionary dream to the spiritual in any way whatsoever. In that case, you are not thinking interculturally. So I’m not saying you have to believe or even understand it—you just have to take it seriously.

TVM: I totally agree. It’s a patronizing epistemology. People will emphasize the colonialist history of missionary Christianity and assume that entails that all religion is colonialist, or that colonized people’s religion cannot be anything but a manifestation of being subjected to Western mores. So I really like the extent to which you dwell on Christianity and process theology in the book. I think it’s very timely. And in particular, disability theory calls upon us to interrogate secular scientism insofar as it problematizes the disabled body. So your Alcoholics and the Imago Dei reflections are very gripping to me, and I especially recommend that chapter to our readers.

Abolition

TVM: When I read the book, I could feel the buildup toward decarceralism. That’s where it ended up, which framed the project well. So, again—long question here.

There’s this back-and-forth in philosophy about incarceration. Let’s say some person, X, is harming people and will continue unless sequestered away. Some philosophers think punishing X is broadly acceptable. Other philosophers—usually hard determinists, or people who are eliminativist about moral responsibility for other reasons—say penalizing X is problematic because X isn’t culpable for hurting people. Saul Smilansky, who is in the first group, raises the following reductio: if we can’t punish X because they’re not really at fault, then we should put them in a nice hotel. He calls this “funishment.” Then he proceeds to say: “Oh no! If that were the case, everyone would want to be there, so everyone would commit crimes, and society would collapse.” Then there have been philosophers from the other camp, Derk Pereboom and Neil Levy for instance, who respond. Some of them don’t think funishment is obviously self-defeating; others don’t think their theory requires it. But at root they agree that we might not have to provide 5-star amenities to X, but we have to treat them kindly.

Levy critiques the thought experiment for presupposing that the (largely financial) costs of funishment are independent of the size of the population that must be funished. More generally, he disagrees with the notion that “funishment” is the model of response to wrongdoing that the eliminativist would want in the first place. In a recent paper, I raise a similar worry. I am afraid the premise of the debate incorrectly assumes that there is in fact some way of sequestering X from other people that isn’t wrong. Even “funishment,” conceptualized originally as so ridiculously great that everyone would want in on it, is morally unacceptable under current conditions of discrimination. The problem is that abolitionist philosophy is overfocused on making the phenomenological experience of being quarantined away from people less unpleasant. It’s a very individualist lens of analysis. But as long as there exist marginalized groups that are agitating for liberation, the prospect of separating out members of those groups disproportionately—even if they have the time of their lives while so sequestered—frustrates the solidarity project. There is no such thing as value-neutral “incapacitation,” or even catch-and-release rehabilitation, that does not perpetuate the thing I call intergenerational erasure.

In your discussion of abolition, you highlight how current proposals do not sufficiently consider addict interests. You criticize the bifurcation often made from the ostensible standpoint of compassion: there are recreational drug users, and then there are addicts who need to be given medical treatment. I’m sure we agree that uncritically continuing to imprison nonaddict users is bad, but I wonder what you think of my general concern above: this “compassionate care” is also harmful to addicts, insofar as it involves their being taken away from communities. I don’t think it matters what institutions are pulling individual addicts away from communities. Hospitals or jails—either way, the absence of a disproportionate number of us makes it so that the rest of us cannot agitate effectively.

WAS: I never thought of it like that. I do agree, particularly given that I am kept alive by other addicts, in a recovery community. Sometimes I find myself thinking about the apocalypse. One of the things that scares me most is, “What if I can’t find any addicts there? How will I stay alive?” So as someone who owes their life, on a really visceral level, to other alcoholics: when you frame it like that, I have a strong negative reaction to that sort of separation.

Of course, addicts being who we are, we form the communities we can form inside and outside of prisons and institutions alike. But that’s making the best out of a bad situation; it’s still unjust. And those are just the lucky ones among us, who are able to do that. We should not be separated in those ways, even if it were going to a five-star hotel, living large but isolated.

TVM: One of the reasons sobriety communities are so transgressive (even though it’s vogue to say otherwise) is that the received view is that we need to be put into institutions, put on IVs, monitored by guys in lab coats taking notes. The view of addiction as a public health crisis combines with the cultural paradigm on which disabled people are perceived with the medical gaze, which foments a very individualizing treatment. Separate little beds, separate rooms. And the epistemological locus is outside the community: it’s the doctor who knows best.

WAS: It makes me think about Brazil, where they were talking about a medical injection that prevents cocaine from producing its psychoactive effects. This was floated as a treatment for addiction. Which is really just another way of controlling drug-using populations, a horrifying continuation of the history thereof.

TVM: Have you been following the discourse about Ozempic as a panacea for addiction? Just this general fascination with the idea that this drug could solve, could cure, addiction. You cite Eli Clare a lot, so I imagine you have some thoughts.

WAS: A little bit. The fascination with cure deviates the gaze from the problem at hand, and from the ways in which addicts specifically can and do care for ourselves and each other.

Radical sobriety and mutual aid

TVM: One of the really great things about this interview and your book, Waithera, is your emphasis on the way in which sobriety can be radical. I love that. I get very annoyed with nonaddicts who uncritically talk badly about addict recovery communities, be it AA or ministries or self-organized sober houses or whatever. I find it so pompous.

WAS: It’s condescending. There are, obviously, ways that mechanisms like AA have been coopted by the state. But the patronizing attitude is not reducible to that. Maybe it’s unfair or ungenerous, but I can’t help but wonder if some of it comes from a contempt for addicts.

TVM: I think you’re right, and that in particular it’s the idea that addicts could claim to have a way of living that has things figured out. Part of the reason it bothers people is the tendency to see addicts as just a mess, fundamentally needing to be overseen by others. There’s other stuff at work too. People assume recovery communities must be basically Protestant. So there’s a contempt for Christianity, as we’ve discussed. And the sense, “oh, this must just be a replacement addiction—you’ve become addicted to this spiritual lifestyle.” But ultimately I think the anti-sobriety sentiment stems from the interpretation of “prudishness” as moral repression: conformist, self-hating. The idea, I think, is that active addiction is to one side of the Aristotelian mean, and abstinence the other extreme. This is why my definition of addict is not normatively excessive substance use, but normatively atypical use. It’s not just addicts’ use patterns but our disuse patterns as well that are transgressive—the fact that for so many of us it’s all-or-nothing. “You’re either going to black out always or never drink again? Why can’t you just drink normally?” It’s inextricable from addict oppression. So probably my single favorite thing in the book is your framing of your recovery community—it really comes across as a subversive, revolutionary endeavor.

WAS: It absolutely is subversive! Sobriety is so often just seen as a way of getting people to be normal, and that’s all that it could possibly be. Someone becomes sober, and then, it’s assumed, they’re able to participate in society in the ways they’re supposed to participate. But that misses so much.

Honestly, like I say in the book, I’m not one of those people who can call myself a grateful alcoholic. I have a knee-jerk negative reaction to hearing myself say I’m grateful for this. If I could have chosen, I would have chosen differently. It’s not that I wish I could drink, but rather there’s a part of me to which the sheer misery of my experience feels unjustifiable. There’s something that feels wrong about expressing gratitude for the destitution that active addiction was for me and is for countless others.

I guess it’s a contradiction, but even as I say that, I am grateful when I think about how different my life would be if not for the experience of sobriety. Sobriety is radical to me because it taught me about mutual aid. In a way that is very visceral, it makes me feel a different world is possible—really, actually, genuinely possible. When I see how my recovery community organizes itself, I have hope. There are so many issues with it constantly; it’s chaotic. But without this example, I would be prone to nihilism, to despair, to the sense that it isn’t possible. I look at my recovery community and I know that a new world is possible. It has made me more discontented with the way the world is today—I would have been pretty discontented anyways—but it’s also given me a commitment to happiness, a belief that my life can be more even than I would have wanted for it. It has taught me I’m not always the best judge of what makes me happy. I think if it weren’t for my alcoholism, the “corporate” sort of life might have been enough for me. I wouldn’t see all the ways in which it takes from me. I don’t know that I’d want as much for myself as I do now, if it weren’t for addiction and sobriety.

My relationship to this identity and community is inherently political. It’s not just the near-death experience element of addiction that made me discontented with this world and committed to a better one. I see all the ways in which the world is not ideal, to put it lightly, through not just my experience but my community. And I see how a new world is possible because of the ways in which addicts in communities work together to create one. That has changed me, fundamentally.

TVM: I understand that. There is a weird tension in the notion of gratitude about being a member of a marginalized group in general. Especially in the case of being an addict, where, to the vast majority of us, unspeakably terrible things have happened.

In your work, I think you illustrate what the positives are in a way that doesn’t seem to imply “therefore I should be grateful for all these terrible oppressions I have suffered.” The way you describe the hope that comes out of your involvement in your community: this is what mutual aid looks like. It comes across also in your Shame chapter, which—sorry to spoil for readers—does not end up being about shame. Your discussion of the productiveness and generativeness of being human with each other, that experiences that start in shame build together through this radical meeting of eyes with one another. I found that very cathartic to read. That’s also the mutual aid I know—I read that chapter and thought “This is exactly what it feels like, and this is precisely the thing for which I am grateful.”

WAS: It’s not so much that I think we have to make every negative affect or emotion productive. It’s just that part of building a new world is finding something to do with the negative affects. Currently, there’s the trend of “toxic positivity” and suppression, and there are many reasons why that emerges. Sometimes it’s a coping mechanism. Building a new world requires recognizing that we will continue to feel these emotions, because they are very human. There are certain narratives now about what we should do with them. Those narratives are political, or can be politicized, even if they don’t feel political. What are we doing to do with them? What might we do with them? So, that chapter is one example I give in the book of what we do with negative affects, and how we’re already doing that.

TVM: I came away from that chapter feeling really convinced that shame facilitates honest reckoning with each other. That doesn’t necessarily mean any and all instances of feeling shame, let alone of shaming others, are good. But it gives us something to do. Investigating this role of shame reveals a small piece of the blueprint for the new world—of how to get there, or what this experience will do for us when we are there.

There’s a great deal of literature about politicizing alcohol and drugs. There’s Dian Million on Indigenous politics, there’s a lot on Black drug use and racial capitalism, and there’s plenty about the subversiveness of drug use. But there really isn’t discussion of radical sobriety. I mean, I’m sure there are four straightedge Marxists who are writing punk songs about it in Bristol. But your work was the first time I’ve seen anyone interpret addict community through the lens of mutual aid explicitly. It had never occurred to me to think about the reinterpretation of one’s self and one’s community through shame, to operationalize my shame to de-individualize myself and understand myself in relation to other addicts explicitly. That’s why devising hermeneutics for ourselves is so important! The lack of discussion is a result, at least partly, of the privileging of the nonaddict standpoint.

WAS: There’s a line in Beloved where Toni Morrison is talking about history and she writes, “All of it is now.”2 And she’s talking about how the slave trade is very much still now. But from specifically the addict perspective, to hear “All of it is now” makes me think that the future is also now. There are experiments we are creating now that are of the future, are of this new world. So in terms of new ways of dealing with negative affects, or looking at how the ways we are already dealing with them are evocative of a new world: shame is a tricky emotion. There are many ways in which it’s been made deeply unproductive and dangerous. But it was such a big part of my own experience that I don’t think I could have written the book without referencing it, even centering it.

TVM: Waithera, thanks so much for interviewing with me. This has been so lovely, and I strongly recommend your wonderful book Through an Addict’s Looking Glass to all of our subscribers.

Sebatindira, “Introduction,” p. 10.

“All of it is now it is always now there will never be a time when I am not crouching and watching others who are crouching too I am always crouching” (210).